Assessments of Value in Everyday Life

If you have ever experienced hope or regret, you know that people's relentless drive to improve their experience is not confined to the present. Attempts to shape past experience are naturally pointless, but being aware of the future to come allows us to shape our experience in a very special way. I am talking about our ability to make trade-offs, moments when we sacrifice our experience in the short-term in order to achieve a future goal. Be it closing a sale, going on vacation, or owning a new home, goals are experiences that we seek to attain in the future; they are experiential ‘destinations’ that we pursue by choice or by duty.

Framing goals as experiential destinations can help us understand them better because we can apply the same logic we use to move through space. After all, physical destinations and the journeys we make to reach them are themselves fully experiential: The value we see in reaching a destination is no other than the value we see in the experiences it enables, in the scenes, the activities, and the people it makes available to observe and interact with. In similar fashion, the journey required to reach a destination is experiential in nature; on our way to a destination we get to experience a mix of natural and built environment, with streets to be crossed, doors to be opened, stairs to be climbed, and people to be greeted.

To start getting acquainted with experiential destinations, think of a place that you would like to visit this weekend; it could be a shop, a park, or the home of one of your relatives or friends.

Is it possible to get there?

An essential condition for a destination to be reachable is that there must be a path that leads to it. Just as people cannot simply teleport to a place, you cannot achieve a goal you consider worthwhile just by thinking of it. Like their physical counterparts, reaching an experiential destination necessitates a path, a ‘set of experiences’ you must go through before and in order to attain the experience we are seeking.

Do you know how to get there?

If a destination (experiential, physical) is reachable, there may be more than one path leading to it. If you do not know a path, you can always take the lead and find a path yourself or ask someone who knows how to get there. If this is a recurring destination, you may even feel inclined to explore new ways to get there.

Is the journey worth it?

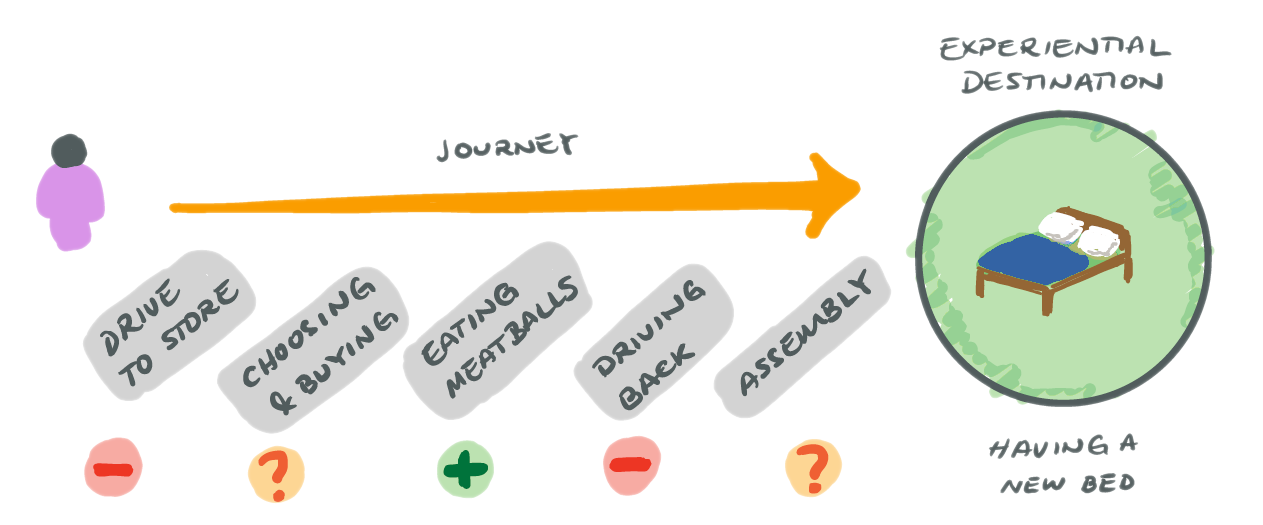

Before getting on the way to your destination, you can ask yourself if the journey is even worth making. Remember that journeys are sacrifices, and as such they usually contain experiences that we would choose to avoid if we were given the option. People make journeys they consider worthwhile, that's why they perform an assessment of value before embarking on them. This is a mental process in which we make a forward projection and tally the experiences we expect to encounter in the way, some of them negative, some others positive, and compare them with the reward we see in reaching our destination. For example, evaluating a trip to to buy new furniture at Ikea could look like this:

A simplified view of the journey to get a new bed from Ikea.

A simplified view of the journey to get a new bed from Ikea.You can think of the experiences that tally negatively in people's assessments of value (e.g., finding parking, standing in line at checkout) as experiential costs. Expecting significant costs or encountering them along the way can make us think twice if the journey is worth it, sometimes to the point of convincing us that it is not. You can also think of these costs as ‘frictions’ – experiential burdens or inefficiencies that, just like mechanical friction, hold us back and make us spend additional time and resources before we achieve our goal.

But which path to take?

If you are aware of multiple possible paths to a destination, you'll feel a natural inclination to select the path that you consider the most experientially favorable or less ‘experientially costly’. In doing so, it's as if our minds were solving optimization problema, computations where we seek experiential reward at the lowest experiential cost. But don't let this optimization framing fool you, the computations made by our brains are nothing short of magical (not even computations at all!). Choosing the less costly between two similar experiences (e.g., walking ten blocks vs. walking five) may seem straightforward, but choosing between tangibly different experiences (e.g., contacting customer support on the phone vs. doing so through e-mail) involves comparing them across more than one dimension. Performing multiple such comparisons can make decisions very difficult.

As discussed in Experiential Value, value is a highly personal and contextual construct. People operate under different drives and different pressures, with different knowledge and abilities. As such, an experience that is costly for you may feel less costly or not costly at all to someone else. For example, the assembly required on furniture or the cooking required to have dinner at home could be or not be frictional experiences depending on who you are and the mood you are in. However, as individualized as perceptions of value may be, there seems to be some consensus on the frictional nature of some experiences. For instance, you can intuitively agree that not many people consider waiting in line or washing dishes to be immediately desirable experiences.

Another thing to consider is that we do not always optimize for efficiency of simplicity. For instance, consider a situation in which you get to decide between two possible paths to get to a store. One of the paths is short but ‘dull’, the other one is ‘scenic’ but longer.

- The first path is the shortest, the second one the most pleasant. Which one would you take?

Which path would you pick? With a flexible context, both options are reasonable. It was during the eighties that business school professors Elizabeth C. Hirschman (New York University) and Morris B. Holbrook (Columbia University ✼) observed that there is a class of products that we consume based on their ability to deliver "fantasies, feelings, and fun". They introduced the concept of hedonic consumption. From their 1982 paper:

"Hedonic consumption designates those facets of consumer behavior that relate to the multi-sensory, fantasy and emotive aspects of one's experience with products."

Consumer choice, they saw, is not driven purely by a product's utilitarian features like speed and performance, there is also value in a product being ‘pleasing’ to our senses and our minds. This condition shines light on the different ways an experiential journey can be evaluated: There is of course a utilitarian way, in which we look to reduce the friction we get to experience; but there is also a hedonic way, where we look for experiential ‘rewards’ along the journey.

Generally speaking, people approach assessments of value in a utilitarian way when they operate under a pressure, a stress, or a resource constraint. In the absence of pressures or constraints, we naturally take a hedonic approach. In the example above, the shortest path would be the obvious choice if you were in a hurry or tired. The scenic path, on the other hand, would be perfect for a Sunday afternoon where you have nothing else to do.

What are your priorities?

Because experience is multidimensional, raw, and total, gazing into the future to compare the costs and rewards of tangibly different experiences within and across multiple paths is fundamentally complex. That is why, even after running your assessments, you may feel indecisive about which path to take (Hello Libra!). This is specially true when your options offer a similar mix of experiential costs and rewards.

To break a tie, you can always compare the paths further to account for overlooked experiences or try evaluating the paths under a new criterion. But performing these evaluations can be real burdensome, sometimes burdensome enough for us to decide to stop thinking and rush a decision based on what we already know.

Can you get help along the way?

There is often people willing to help you get through. Just as we use cars, bikes, and escalators on our way to physical destinations, the modern economy offers a multitude of products and services to make our experiential journeys more bearable and sometimes even enjoyable. This discussion starts in Reducing Friction.

Perceived Value vs. Actual Value

Remember that while we choose our journeys based on perceived value, the actual value we derive from the experiences in the journey may differ from expectation. There is always so much that is beyond our control and it is not until you get to feel the actual journey that you discover just how costly it is. The same happens with the rewards we expect to find at the destination; it is not until you get there that you can tell how accurate your expectations were.

Whenever there is a mismatch between expected and actual costs or rewards, our perceptions of value are adjusted. It is through these cycles of expectation-realization-adjustment that our assessments of value become more than mere additions and subtractions, but indeed a reflection of the self and the sum of our past experience.

✎ Connection to

Key / The Human Sense of Value