The High Line Ignores Chelsea

Since opening in June 2009, the High Line has become an icon of American contemporary landscape architecture. The High Line's success has inspired cities throughout the United States to redevelop obsolete infrastructure as public space. The park became a tourist attraction and spurred real estate development in adjacent neighborhoods, increasing real-estate values and prices along the route. By September 2014, the park had nearly five million visitors annually, and by 2019, it had eight million visitors per year. (Wikipedia, 2022)

There's no debate, by numbers The High Line is a success to be celebrated. But numbers have a way of hiding the truth. Feet on the ground, a visit through the park reveals what's missing: Across one and a half miles and 19 street crossings, the park provides little to no opportunities to connect with the neighborhoods and businesses underneath. From start to end, you are seldom invited to reach out beyond the path. As an experience, The High Line exists on its own.

A High Line Experience

If you recorded your experience at the High Line, the story would be very monotonous. You typically enter by the South using the access next to the Whitney Museum or from the North at the junction with Hudson Yards. No matter which direction, the experience of traversing the park feels like pilgrimage to nowhere. Partly to blame is the silent expectation you be in constant movement lest you become an obstacle; stopping for a couple breaths puts you in the immediate way of fellow visitors. A flow constricted with no release, very choreful.

A gate marks the entrance to the High Line from Hudson Yards.

A gate marks the entrance to the High Line from Hudson Yards.When you enter the park from the North, you start with a nice wide curve that offers a sense of space that gets you situated. But after that it's all narrowness and flux and voyeurism. Luxury Condos sprouted all over, arguably wishing to bank on the High Line as a unique selling point. It's very hard to ignore, the dialogue established while walking on the park and the windows of neighboring residences. You're invited to "peek into the life". It's a very powerful feeling all the way through.

You keep walking and a sense of expectation is built with every step. First time, you start wondering where the path might lead. If life has taught you anything it's that walking leads somewhere, but all throughout you find little release. Breathing space is limited, the park is an open tunnel.

Stairwell connecting to 26th Street. There's an obvious gap in the level of care put in the park's landscaping and the interfaces connecting it to the city.

Stairwell connecting to 26th Street. There's an obvious gap in the level of care put in the park's landscaping and the interfaces connecting it to the city.It's precisely the lack of breathing space — space to be and do what you will — which makes it all the more meaningful to ask... why isn't the High Line properly integrated with the space under it? Streets downstairs need some love but they aren't made "part of" the overall dynamic. The High Line experience "doesn't include" or invite a casual interaction with neighboring businesses. The stairwell at 26th Street is witness: When you leave, it feels as if you were leaving for good. The aura is of an emergency exit or a correctional facility.

Looking down to 23rd Street from the High Line.

Looking down to 23rd Street from the High Line.But it's not until you reach 23rd Street that you can feel the first big missed opportunity. Towards the East, you have this wide, beautiful street flanked by trees, sharing a view of the Hudson River park to the West, and you have all these businesses under you. The street has wide sidewalks that would've been happy to accommodate a real staircase, a visible sign of integration inviting you to step down the park for a moment to interact with community below. Instead, the stairs at 23rd feel clandestine, just like every other access point to the park. It's as if the entrance were not being celebrated but frowned upon. A style too subtle, too casual, too cool to harmonize with the neighborhood below.

Visitors taking pictures against the backdrop at 23rd Street.

Visitors taking pictures against the backdrop at 23rd Street.The park does offer nice views of the city. In fact, every time you cross above a street, the real outcome is the same: People are afforded an opportunity to stop and lean against the rails to take pictures of a city backdrop they can't access in dignified manner. Scenery for an Instagram story, that's the main way to interact with the High Line other than walking through it.

By the time you reach 21st Street the monotony becomes obvious and the logic of the dynamic is revealed: You're walking in order to reach the next crossing, hoping it will offer a worthwhile view... Speaks loudly of our visual culture, an obsession exacerbated by cameras.

The Lantern House adorns the High Line with mesmerizing design.

The Lantern House adorns the High Line with mesmerizing design.Keep walking and you soon encounter a beautiful building, honeycomb-like. It's the "Lantern House", a high-end residential project commissioned by Related Companies to Thomas Heatherwick. It's crazy how they're behind all things around here... the Vessel, the High Line, Little Island, all of them projects backed by the same circles and mentalities. More telling perhaps is the private gate giving the Lantern House direct, deck-level access to the High Line, a rare dignity and a taste of the possibilities missed across the park.

A private gate connects Heatherwick's Lantern House to the High Line.

A private gate connects Heatherwick's Lantern House to the High Line.

It's just after passing the Lantern House that missed opportunities get real. The High Line's crossing at 17th Street is special, a diagonal tract that breaks monotony and affords sense of place, brought together by an undeveloped parcel underneath. However beautifully landscaped, it's clear this crossing asked for something more than an elevated walkway. The design team's anxiety to achieve something here can be felt in the form of the nook they built right off the corner of 17th, across from Artichoke Pizza. The nook provides seating and an actual glass window where you can admire the parade of cars below, a feature that develops the same voyeuristic relationship with the surroundings established throughout the park. No interaction, only observation.

The High Line's nook, overlooking its crossing with 17th Street.

The High Line's nook, overlooking its crossing with 17th Street.

You keep walking South past the nook and you reach the segment where the High Line crosses through the Chelsea Market building. The deck widens and makes space for a couple concession stands offering drinks and snacks, as if trying to make up for the lack of refreshment options in the park. Hudson Yards comes to mind... like them, the High Line needs a team coordinating the availability of concessions that serve only High Line visitors and over which the High Line has ultimate control.

The High Line crosses through the Chelsea Market building without further interaction. (Gryffindor, Wikimedia Commons)

The High Line crosses through the Chelsea Market building without further interaction. (Gryffindor, Wikimedia Commons)

Establishing linkages to the Chelsea Market would seem obvious, but things in the United States can get litigious pretty quickly. In compassionate light, the High Line may have simply tried to avoid the legal risks of establishing a relationship with its surroundings, because every time a relationship is established there is a back and forth, a pulling and pushing of how value is shared. By severing potential interactions with the community, the High Line established a legal shield of sorts, at the expense of the harmony of the city and the space that it serves.

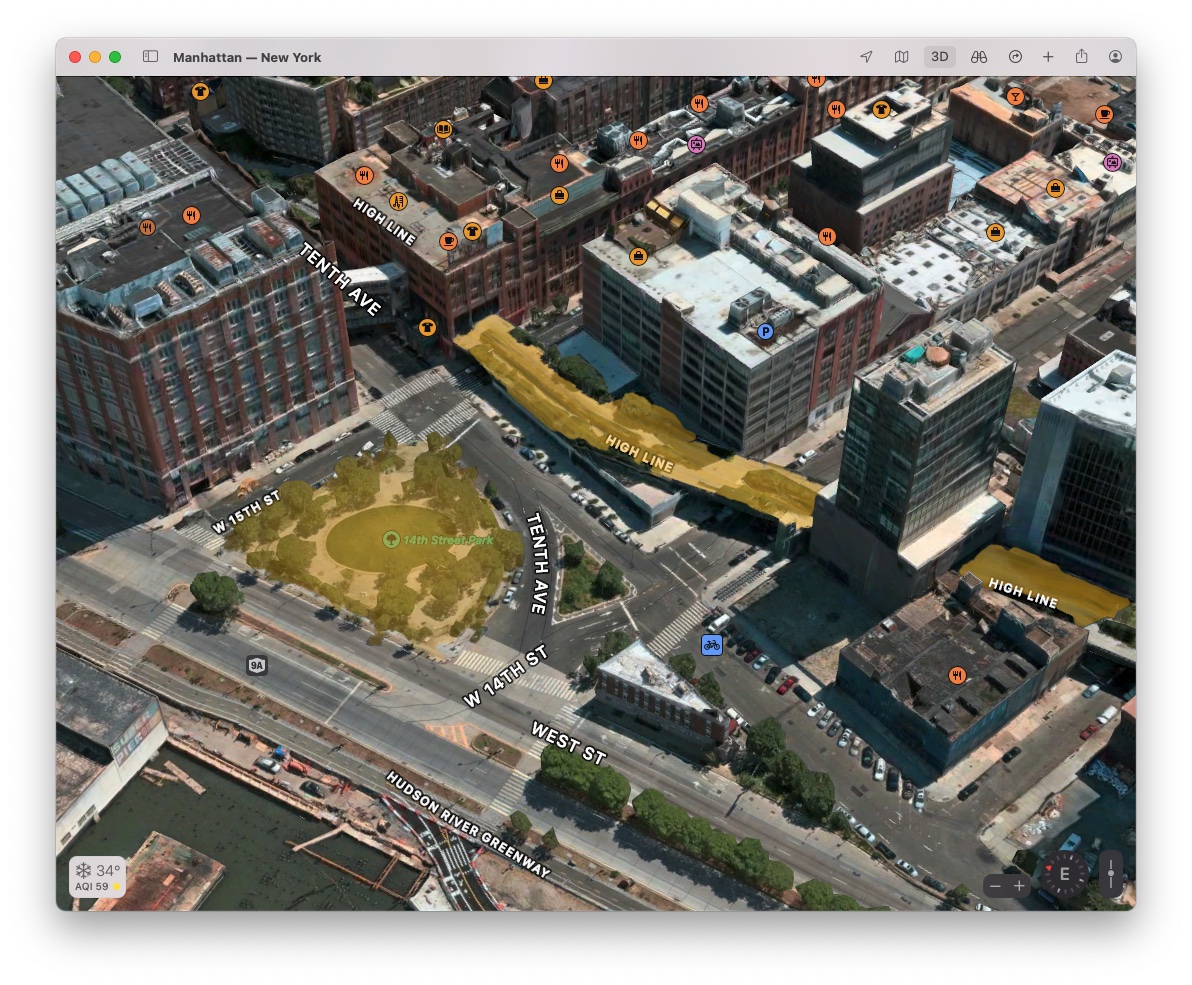

The park at 14th Street could serve as a grand entryway that brings the High Line closer to the Hudson River and Little Island.

The park at 14th Street could serve as a grand entryway that brings the High Line closer to the Hudson River and Little Island.

After this it's all déjà vu. The crossing over 14th Street mirrors the promise of the nook three streets above, with a neighboring park clamoring for union, the only clear shot at integrating the Hudson River Park to the High Line. To the East, the neighborhood of Chelsea is almost disregarded. Full of art galleries and food establishments, it could've been leveraged to offer release to park visitors while making the place feel more together. Instead, rumor has it locals see the High Line's separateness as a blessing, keeping tourists out of the cherished neighborhood.

Very little connection between the High Line and the neighborhood of Chelsea.

Very little connection between the High Line and the neighborhood of Chelsea.

The journey ends a couple streets down at Gansevoort Street, where the High Line meets the Whitney Museum of American Art. The access point here is really the only one that exhibits proper integration: The staircase between deck and street level has a flyby section that invites visual connection with the space, giving you room to select your next destination as you come down.

Missing Beauty

There's a beauty missing in the High Line. We can blame much of the park's breathing room problem on the context and history of the site. The elevated track was originally conceived to take just enough room for the railroad, no more. The resolve of the authors of the High Line to reclaim this space for public enjoyment despite the obvious limitations is nothing short of courageous. Still, it's evident there's so much that wasn't done, promises that can still become realized.

High caliber spatial interventions like the High Line are rare and expensive, projects burdened at birth with an expectation they'll breathe new life into everything around them. You don't see that with the High Line, you don't see a unifying tract making Chelsea and the West Side a bigger whole. How do you harmonize at such a large scale using a central logic? The High Line has a harmony problem, the park won't pour onto the streets.

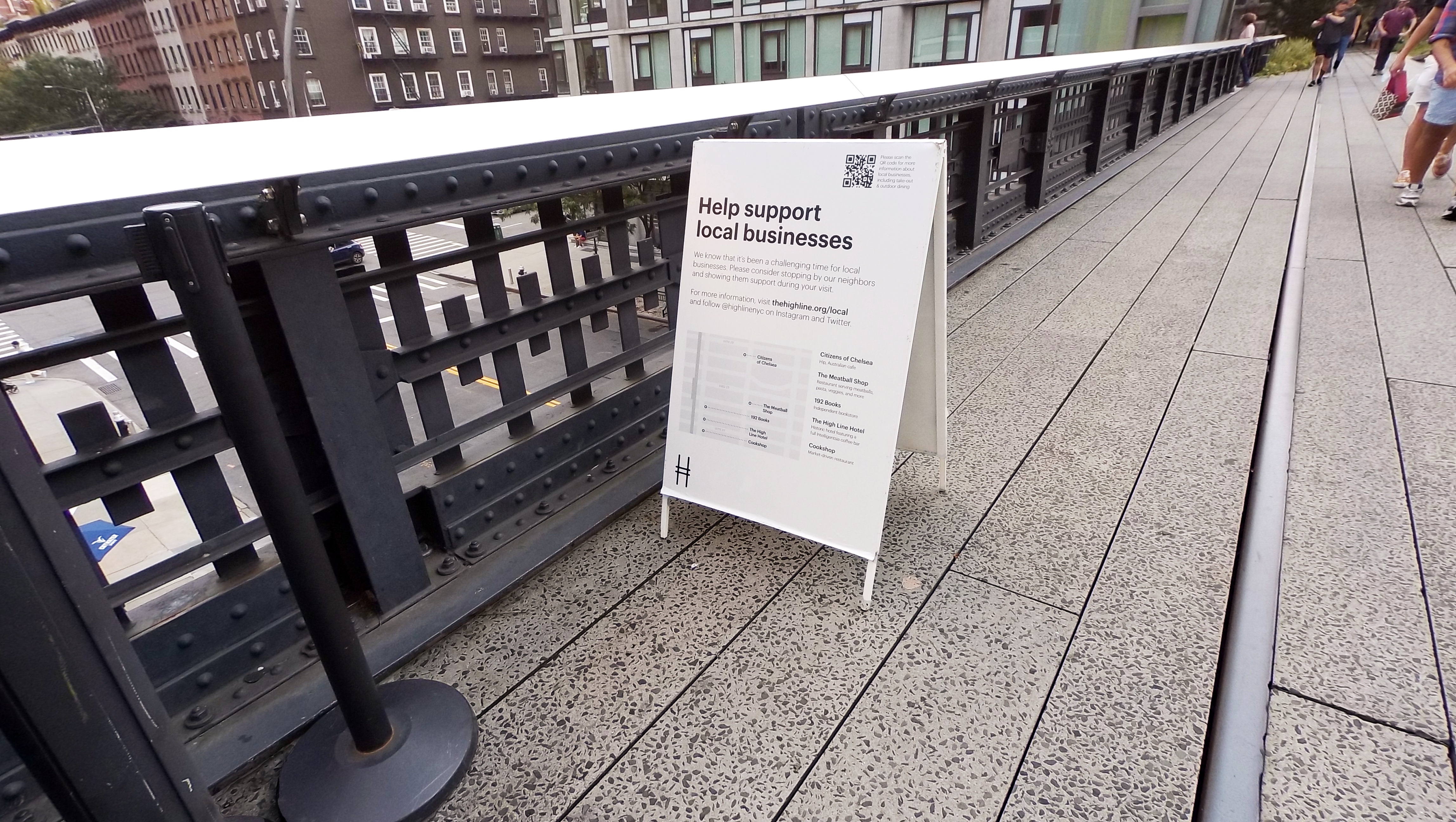

A sign is not enough.

A sign is not enough.That's why projects like these are controversial, because the stakes are too high. It's too much responsibility, for a handful of design firms to transform the fates of entire communities... perhaps too much. They say crowds are hard to please, and it's hard to exercise such a power without a credible expectation the outcome won't seriously betray at least some hopes and expectations.

And yet there's plenty of room for redemption. Only so much can be achieved in a single stroke and the High Line has already achieved a lot. Every time we build something, it's a victory. Each instance of creation is a victory claimed over a feeling that something beautiful was missing. When there's a beauty clearly absent... that's the only call to action you need.

✎ Connection to