The Commercial Supply of Value

American economists Joseph Pine II and James Gilmore open their 1998 book "The Experience Economy" with the following example:

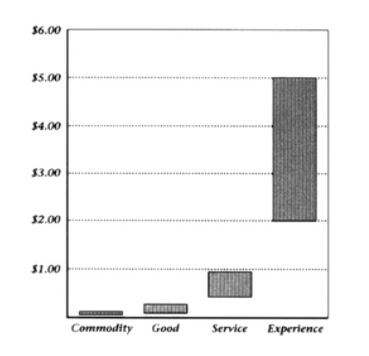

"Consider a true commodity: the coffee bean. Companies that harvest coffee or trade it on the futures market receive — at the time of this writing — a little more than $1 per pound, which translates into one or two cents a cup. When a manufacturer grinds, packages, and sells those same beans in a grocery store, turning them into a good, the price to a consumer jumps to between 5 and 25 cents a cup (depending on brand and package size). Brew the ground beans in a run-of-the-mill diner, corner coffee shop, or bodega and that service now sells for 50 cents to a dollar per cup. But wait: Serve that same coffee in a five-star restaurant or espresso bar, where the ordering, creation, and consumption of the cup embodies a heightened ambience or sense of theatre, and consumers gladly pay anywhere from $2 to $5 for each cup."

Value-add across the coffee supply chain.

Value-add across the coffee supply chain.

People, they observed, had a much higher willingness to pay for products and services if they were delivered in the form of a ‘staged experience’. This, in turn, led them to claim that experience was a ‘new source of value’ and a ‘new genre of economic output’. But it was neither. What Pine and Gilmore thought to be a new and distinct economic offering was, in fact, the only source of value people can know – and by describing what they deemed to be a new ‘experience economy’, they were describing the only economy we have ever had.

The Nature of the Economy is Experiential

The 20th century saw a wave of growing awareness on the experiential nature of economic value. Not long after Holbrook's and Hirshman's 1982 work on hedonic consumption there was Donald Norman's push for ‘human-centered’ design, which culminated in his popular book "The Design of Everyday Things". In his book, Norman argued for a design practice that encompassed the ‘entire experience’ of using products:

"(We have to) ensure that the products actually fulfill human needs while being understandable and usable. In the best of cases, the products should also be delightful and enjoyable."

In 1992, German sociologist Gerhard Schulze published his book Die Erlebnisgesellschaft ("The Experience Society"), an account on how people of the German city of Nuremberg – newly rebuilt and prosperous – spent their days in parks, markets, and cultural venues looking not merely for survival, but for what he called the schönes Leben ("beautiful life"). Pine and Gilmore followed suit with the more business-oriented "The Experience Economy", which helped to spread the idea of experience, a traditional concept of philosophical concern, into corporate halls.

Feeling Reward in Experience

In 2019, the Coachella Music and Arts Festival of Indio, California recorded an attendance of 250,000 people over two weekends, booking revenues of USD $114 million. That same year, 70,000 people congregated in Atlanta, Georgia to watch the Super Bowl LIII, with close to 100 million people joining through television. Meanwhile, on the other side of the world, India's Taj Mahal and the Great Wall of China were each receiving, on average, well over 600,000 visitors per month.

These experiences cost not only money, people also have to endure unreasonable burdens like making ridiculously long lines or sitting on a plane for hours. These experiences do not have a clear utilitarian purpose, so where does the value come from? This is an opportunity to take a deeper look at how value works:

The notion that perception elicits certain ‘responses’ in the human mind is pretty well established in psychology. Collectively known as affect, these responses can be described across many dimensions and require an intricate web of abstract terms to be accurately characterized. To simplify our discussion, however, let's think of affect in terms of two components:

- The first component is comprised by the immediate sensory and emotional consequences of having an experience. Is this experience you are having right now making you feel pleasure or displeasure? Let's call this the affective response.

- The second component is connected to the immediate feeling of attraction or repulsion that you get from the experience. Is this experience drawing you in? Let's call this the appetitive response.

It is not always the case, but affective and appetitive responses often point in the same direction because we are attracted to that which makes us feel good and viceversa. When negative, affective and appetitive responses push us away and make us want to disengage with the experience. Positive responses, on the other hand, keep us in and make us want to engage further. Together, these instinctual responses provide insight into the value of an experience by answering two questions:

- Is this an experience worth having?

- And, is it worth it to continue having?

Affirmative answers to these questions are indicative of value because there is no truer way of attesting to the perceived worth of an experience than your inclination and willingness to have it. Beyond answering these questions, responses also ‘infuse’ experiences with their positive and negative character because they are themselves felt and experienced; they are 'feelings' that blend and become one with the experience that elicited them, making the whole moment experientially feel ‘costly’ or ‘rewarding’ to us.

The Markets of Experiential Reward

In the context of human affectivity, there are two basic ways in which people can create value for themselves and for others. These two ways are 1) providing experiential relief and 2) supplying experiential reward. The first one relates to activities that make life more bearable by avoiding or removing experiences with negative value. The second one is about making life more enjoyable by adding experiences with positive value. You can see it in the economy following suit: In Reducing Friction, we explored how firms and individuals provide experiential relief to people using products and services. Here we'll see how products and services can also deliver experiential reward by appealing to our senses and/or minds.

Products appeal to the senses through their aesthetic and/or organoleptic properties. Fragrances, wine, and specialty foods, for example, deliver pleasant gustatory and olfactory experiences that command price premiums in the market. Services, too, can appeal to the senses by the nature of the interactions between the service provider and the beneficiary of the service. The setting in which the service process develops can also appeal to the senses. Massages, for example, deliver a soothing haptic experience in a calm and relaxing environment. Products and services can also appeal to the mind when they deliver feelings like attraction, validation, belonging, security, self-esteem, and learning. Think, for instance, of clothing that makes you feel good or services that promote balance like psychotherapy and hospitality.

All of this said, you may have noticed that experiences like watching the Super Bowl or spending a day at Disney World defy categorization and cannot be easily tied back to products and services. This is particularly true of the arts, performances, natural spectacles, and architectonic pieces. To talk comfortably about the markets of experiential reward we have to talk about media, a topic covered in Experience Delivery. For now, you can think of media as a ‘source’ of experience.

A Space for Creativity

The world of media is inherently creative and our ability to imagine and architect novel and compelling experiences seems to only be gaining steam. Every new material, new tool, and new technology has the ability to compound with existing media to make new experiential destinations available to the public. The internet, in particular, has brought about a new generation of experiences that has only begun to take shape, along with the ability to deliver them at scale. These are developments we should all feel excited about, for it is our personal pursuit of experiential reward which gives us each the chance of making life our own.

✎ Connection to