Ways and Means to Deliver Experiences

We can think of any commercial firm as an entity that delivers experiences to the public through one or more mediums. But how do you actually ‘deliver’ an experience to a customer? You don't just pack it in a box and drop it at their home address. For the experience to unfold they the customer has to engage your product, they need to interact with it and literally have experiences with it.

This is a conversation that will help you shift your focus from ‘products’ and ‘services’ to the experiences they enable. To get started, let's think in terms of product first. It is a good way to start since products are the dominant vessel in which experiences are delivered nowadays.

Engagement: Delivering the Experience

As if it were a genie in a bottle, products ‘carry’ in them the experiences they were designed to deliver. These experiences can be accessed by the user through interactions with the product. We can also think of interactions in terms of ‘engagement’.

In the context of experience delivery, it can be useful to talk about engagement in addition to interactions because directionality matters. While both concepts convey a sense of mutual enaction, engagement as a term lends itself better to specify interactions where the user engages the product and others where the product engages the user.

In this way, engagement can be used to convey a sense of direction at the time of describing interactions that happen between people and objects. For instance, as a user, the experience offered by a product has three different components:

- The experience of engaging the product (by using it, operating it, disposing of it)

- The experience of being engaged by the product (e.g., when an alarm clock goes off and wakes you up)

- The experience of engaging the world through the product (e.g., using a lighter to light up a cigarette)

A notion of engagement is key to understanding experience delivery because, in the absence of engagement, the experience offered by the product does not develop. Engagement, in this sense, means ‘acting upon’ and can consist of essentially any action that is applicable to the product being engaged.

Affordances: Understanding Possibilities

The realm of possible engagement with any given object consists of a set of relationships called affordances or ‘action possibilities’.

The concept was introduced by American psychologist James Gibson as part of his research in environmental psychology. From his 1979 book:

"The affordances of the environment are what it offers the animal, what it provides or furnishes, either for good or ill. The verb to afford is found in the dictionary, the noun affordance is not. I have made it up. I mean by it something that refers to both the environment and the animal in a way that no existing term does. It implies the complementarity of the animal and the environment." (p. 127)

We can think of affordances as a set of behavioral possibilities or a ‘behavior space’. As a notion it is both beautiful and useful: Thinking in affordances radically changes the conversation because it invites us to talk about the world not for what it is, but for what we can do with it. It transforms descriptions (“there is a swing in the playground”) into possibilities (“in the playground I can swing!”). To Gibson's credit, the concept accomplished much in helping people understand the world in experiential terms.

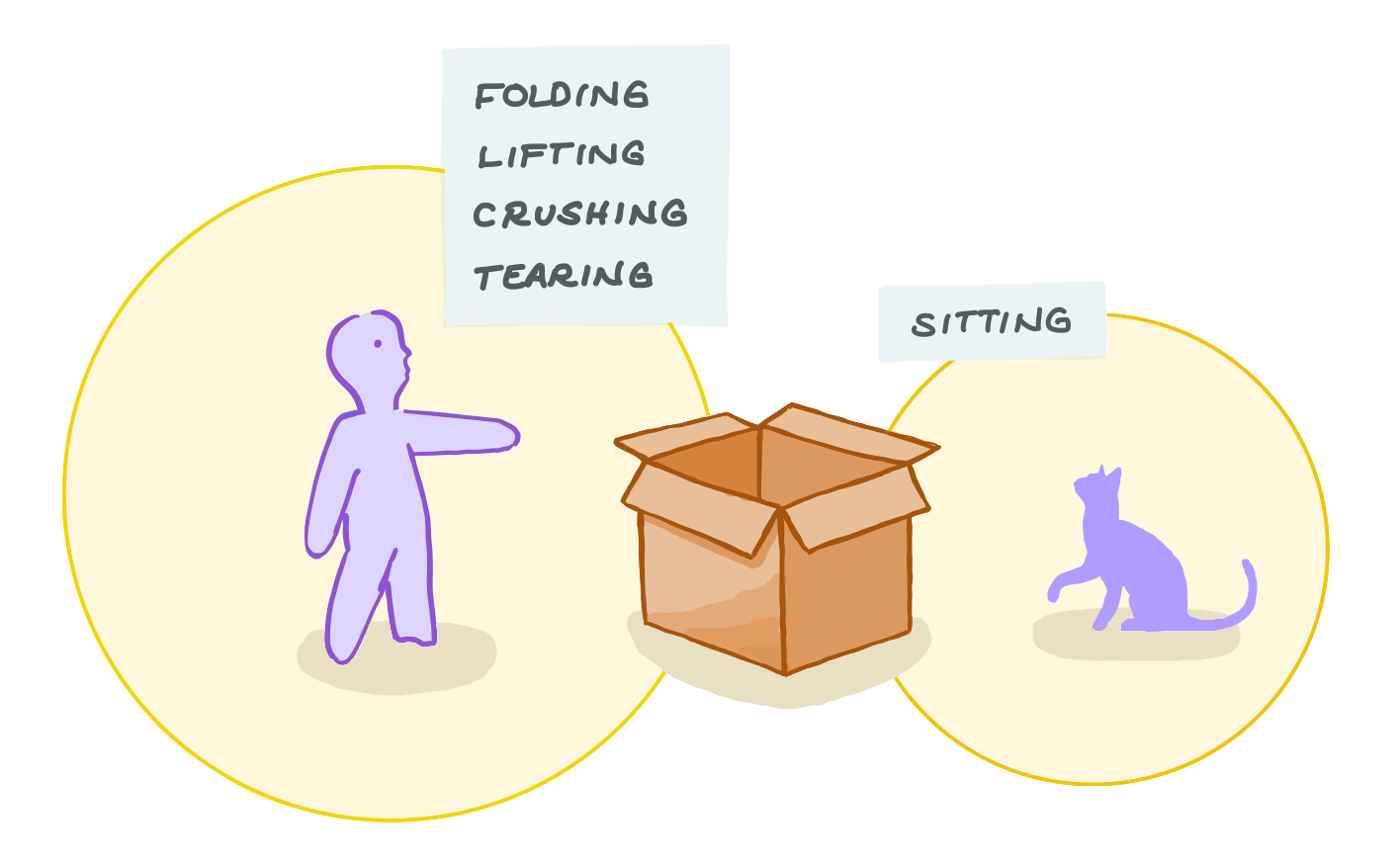

Sample behavior spaces and affordances for a person and a cat in relation to a cardboard box.

Sample behavior spaces and affordances for a person and a cat in relation to a cardboard box.Affordances were popularized as a concept by patron saint of user-centered design Donald Norman in his classic book "The Design of Everyday Things" (originally "The Psychology of Everyday Things"). Norman's embrace of affordances, however, had a twist: Instead of using the term to refer to the set of all actions that are possible with an object, he used it to refer to the action possibilities that could be perceived by the user.

Norman's use of the term makes sense when you consider his thesis: The way in which the user engages a product can be ‘directed’ by making sure the product offers the right affordances and presents them in a way such that they can be readily inferred and understood by the user.

* Note: If you are interested in an in-depth comparison between the affordances of Gibson and Norman, you can consult this article.

The discrepancy was later resolved. Borrowing from the field of semiotics, Norman presented the concept of ‘signifiers’ in a revision of his book. Signifiers, he said, are the qualities of a product that suggest an affordance is available. From the revised and expanded edition of his book:

"People need some way of understanding the product or service they wish to use, some sign of what it is for, what is happening, and what the alternative actions are. People search for clues, for any sign that might help them cope and understand. It is the sign that is important, anything that might signify meaningful information. Designers need to provide these clues. What people need, and what designers must provide, are signifiers." (p. 14)

Signifiers matter because, with any given product, there is engagement that yields better experiences than other. Moreover, products usually require specific types of engagement to deliver the experience they were designed to deliver. Consider your ability of touching, clicking, voice-activating, pulling, pressing, or scrolling on a product; these action possibilities are built into the product ‘by design’ and it is among the responsibilities of the designer to make it so that the you will identify them. If the action possibilities designed into a product are not properly signified, a user may engage with the product in unintended ways, delivering what may be an inferior and qualitatively different experience in detriment of your brand or product.

Attention: First Layer of Engagement

As the focal point of experience, attention is essential to experience delivery. If the user doesn't notice, we can hardly consider an experience to be ‘delivered’. The concept of attention is all the more important because it is a key ingredient in human action and engagement. The relationship between attention and action possibilities is described eloquently by Odmar Neumann, psychologist at the University of Bielefeld in Germany in an essay from 1987:

"Selection is evidently needed for the control of action. Organisms must constantly select what to do and how to do it (...) The problem is how to avoid the behavioral chaos that would result from an attempt to simultaneously perform all possible actions for which sufficient causes exist." (p. 374)

In other words, an action possibility cannot be acted upon if it is not ‘selected’ to be acted upon. That is why all meaningful engagement requires and includes attention. "My experience is what I agree to attend to", wrote William James, one of the founders of modern psychology. From his book "The Principles of Psychology":

"Everyone knows what attention is. It is the taking possession by the mind, in clear and vivid form, of one out of what seem several simultaneously possible objects or trains of thought. Focalization, concentration, of consciousness are of its essence. It implies withdrawal from some things in order to deal effectively with others, and is a condition which has a real opposite in the confused, dazed, scatterbrained state which in French is called distraction, and Zerstreutheit in German ['absent-mindedness' in English]."

In fact, engagement is intrinsically connected to attention because attention is the simplest form of engagement. Remember this the next time you stop looking at a beautiful stranger in the subway the moment they glance back.

You can call ‘attentional engagement’ any form of engagement that consists purely of attention (e.g., visual, auditory, mental). Attentional engagement produces experiences that result from contemplating aspects of Reality and it is what people use to consume experiences offered by media like TV, music, film, books, and performances (e.g., sports, a lecture).

As if it were a scaffold, all other engagement is built on top of attention. You could call engagement that falls in this category ‘higher engagement’. Higher engagement produces experiences that result from acting upon an aspect of Reality (as compared to just paying attention to it). It is the type of engagement people use to experiences things like throwing a ball, holding a conversation, driving a car, or assembling Ikea furniture.

Media: What is it?

The last piece in understanding experience delivery is ‘media’. But what is media? It was briefly discussed in Experiential Rewards, but let's dig deeper. We hear the word so much. It is equally used to refer to books, newspapers, cable news, hard drives, services like Twitter, and materials like paint and brushes. As we know, when a term is used to refer to so many things, it becomes difficult to pinpoint what it refers to specifically.

Media as a term is relatively new and takes its first meanings from the word that is now regarded to be its singular form ("medium"). The Oxford English Dictionary contains citations dating back to the sixteenth century (1500's), when it was used to refer to "a person or thing that acts as an intermediary" (e.g., a means or an instrument) or "a pervading or enveloping substance in which an organism lives". In the late 1600's the notion of medium as "a token of value used in transactions" came about as a natural extension of its conception as an instrument or intermediary.

It was not until the mid 1800's that the idea of medium suffered its first big expansion in meaning. That is when the plural form "media" appeared, along with its usage as "a channel of mass communication" (e.g., newspapers, radio, television). A 2010 study by Professor John Guillory of New York University helps us make sense of the origin of the concept:

"(...) the concept of a medium of communication was absent but wanted for the several centuries prior to its appearance, a lacuna [note: gap] in the philosophical tradition that exerted a distinctive pressure, as if from the future, on early efforts to theorize communication. These early efforts necessarily built on the discourse of the arts, a concept that included not only "fine arts" such as poetry and music but also the ancient arts of rhetoric, logic, and dialectic. The emergence of the media concept in the later nineteenth century was a response to the proliferation of new technical media — such as the telegraph and the phonograph — that could not be assimilated to the older system of the arts." (p. 321)

The emergence of media as an umbrella concept is an achievement of its own. The rise of the personal computer and the Internet in the 1980's and 90's expanded the term even further. By enabling combinations of text, graphics, sounds, and video, personal computing brought new forms like software, animations, video games, and other new interactive content firmly under the umbrella of media, along with the devices that made their consumption possible. The Internet stretched the term even further to include the services that enable the global distribution of digital content and the very Internet itself.

The ever expanding meaning of media demands an articulation for the term that reconciles its many uses. One such articulation came in the 1960's from influential media theorist Marshall McLuhan. He famously declared media to be the "extensions of man" – technological extensions of our senses, bodies, and minds. He applied the term liberally to refer to seemingly disparate things like roads, money, television, radio, light, photographs, amongst others.

Advocating such an aggressive semantic expansion earned McLuhan high-profile criticism. Pioneer of semiotics Umberto Eco, for example, accused McLuhan of playing "games of definition". From the 1986 translation of his essay collection "Travels in Hyper Reality":

"It is not true that—as McLuhan says—all the media are active metaphors because they have the power to translate experience into new forms. In fact, a medium—the spoken language, for example—translates experience into another form because it represents a code. A metaphor, on the contrary, is the replacement, within a code, of one term with another, a simile established and then covered. But the definition of medium as metaphor also covers a confusion in the definition of the medium. To say that it represents an extension of our bodies still means little." (p. 233)

* Note: Read more about how media does, in fact, act as an extension of your mind and body in this essay.

Media is Everything

The tension persists: As evidenced by the word's many uses, the semantic expansion of the term media is real and a unifying conceptualization is missing. Don't get me wrong, semantic broadening happens all the time. The idea of computer, for example, went from "a person who makes calculations or computations" to describe such things as the room-sized mainframe computers of the 1960's. It is now perfectly fit to refer to smartphones, raspberry pis, and tablets but its essence is still the same... all these things are still used to "perform calculations".

Media is different. It is what we consume through a computer and the computer itself. It is the artwork produced by Bob Ross but also the paint on his palette and the videos of him painting. What is the shared essence of media? Here's an expansive new interpretation of the term:

Media is any part of Reality susceptible of being engaged, by means of attention or action, to obtain an experience.

This is precisely why products work as ‘vessels’ for experience delivery. Like everything else, products are media. Media can be physical, mental, or digital. It is the food in your pantry, the clothes in your closet, and the things in your phone. It is the people you know and the buildings in your city, the everyday things of Norman and the forms of Plato, the world around us and the one inside your head. The nature of media as a source of experience gives its semantic expansion only one natural end: To encompass everything that can be experienced.

The function of media is affording experience.

You may have lots of questions and this work is here to provide guidance. In the meantime, please reflect on the meaning of this conversation. Media is what people create, consume, and exchange every day to shape and improve their experience. It is what we spend our lives fighting to own, enjoy, and surround ourselves with. And we are not to blame, because your experience and the experience of those you care for is of the highest importance. The more you understand what you want out of it and about the nature of media itself, the better prepared you'll be to make this journey joyful and fulfilling.

✎ Connection to