The Motivational Role of Media in Human Affairs

New Media: Spice of Life

When you open the spice cabinet in the kitchen, do you ever think about how the contents in the small flasks before you once dominated the world economy? From the rise of the Roman Empire (1st century BCE), to the Middle Ages (5th-15th centuries), and well into the Renaissance (15th-16th centuries), Europe's appetite for spices shaped global commerce and politics in ways that can be felt to this day. The spice trade between Europe and Asia filled the Red and Mediterranean seas with activity, establishing major trade routes and fueling the commerce of other products such as fabrics, timber, and gemstones.

Spices had tremendous value in European markets. It was the spice trade which turned the ancient port of Alexandria into the world's largest commercial center and which elevated medieval Venice into a geopolitical force to be reckoned with. The spice trade was also the motivating force behind the expeditions leading to the bloody European invasion and conquest of the Americas. Control and access to spice-rich territories continued to influence geopolitics even into the 17th century (1600's), playing a role in the 1677 transfer of New York City (formerly "New Amsterdam") from the Dutch to the British.

The events defy modern understanding... Why all the trouble for these now-common pantry items? Historians offer an array of explanations. Some say the motivation was in the spices' ability to cover foul tastes in spoiling food; others point to their curative properties; lastly, there is of course their use as condiments. While there is truth to these accounts, none of them makes a real effort to imagine just how special spices must have been to warrant a dynamic of global conquest and competition. Because, if you asked me, the only reason I would buy to send my people on a treacherous journey across the sea risking hunger, dehydration, and death is for the promise of something magical. From a historically-conscious perspective, thinking of spices as mere 'condiments' is probably a gross understatement.

To me, a more compelling explanation is that – in addition to a magical cure for ailments – spices delivered 'spectacle', but not of the visual kind. Spices offered exquisite and complex organoleptic sensations to a people tired of blandness, delicious experiences previously unavailable and unimagined. Because today spices may be just another cheap commodity, but imagine the surprise of people when they encountered ginger for the first time; surely a wondrous experience. Picture the moment: You find a root (technically a rhizome), but intensely fragrant. You taste it and it has a taste unlike any other, uniquely warm, woody, and sweet, followed by a bite that leaves you wondering if it's pleasant or not, the only way of knowing being to do it again. Most definitely a rare spectacle, the equivalent of a symphony playing in your tongue if you compare to the humble taste of a potato or a yam.

Spices appealed not only to the senses... the fantastic stories used by merchants to conceal their origins also spiced up imaginations. From culinary historian Sarah Peters Kernan:

"Some spices were legitimately difficult to harvest. Musk, an oil from the scent glands of a Central Eurasian deer, and ambergris, a waxy substance produced by the digestive system of the sperm whale, were two such spices. Others, however, were more easily procured. Yet merchants assigned bizarre stories to other spices to heighten their value for European consumers. Since most people in the medieval West had no contact with the Far East and the actual origins of spices, these myths persisted for centuries. The two most notable of these are tied to pepper and cinnamon. Pepper was said to be guarded by serpents which had to be chased away by fire. This fire turned fresh, white peppercorns into black, wrinkled spices. Walter Bayley mentions this legend in the excerpt from his treatise on pepper. Cinnamon had a similarly wild story. Merchants claimed that a mythical bird called a Cinnamologus made nests out of cinnamon sticks in Arabia. These nests were built on perilous cliffs, and people had to drive the birds from these nests in order to harvest the cinnamon."

By offering an exotic array of bodily sensations infused with a mental sense of amazement and fantasy, spices delivered an experience worthy of kings. No wonder pepper sold for the equivalent of a week of 'unskilled' labor in twelfth-century London (1100's). In perspective, a 40-hour week at minimum wage in the United States ($7.25 US Dollars/hour) is worth $290 dollars, roughly the price of a ticket to a top-tier Broadway performance or a major music festival.

It is by looking through a lens that remembers that people in the past were irreparably deprived of modern experiences that our history of fascination with products like tobacco, opium, cacao, and rubber starts taking color. Experiencing awe, wonder, and fascination was as valuable and popular then as it is now [they felt it first!].

Like us, ancient peoples hungered for new experiences; unlike us, they couldn't get them on demand – supply was limited. You could look up to the sky and test your patience, you could throw yourself into risky adventure, or you could resort to the safety of your imagination. This may be the reason why exploration was considered such an important enterprise. Expeditions were a serious affair with implications for collective experiential well-being. They were also an avenue to an exciting life, a statement of courage, and an opportunity to become legend. Exploration supplied society not only with discoveries of natural wonders, new species, and magical substances, but also with reverberations of the adventures themselves in the form of stories. Together with the arts, these stories must have been a precious source of amusement and amazement.

New Stories need New Media

If the concept of new media doesn't make you think about spices and instead makes you think about such things like augmented-reality glasses and the latest social media, you are not alone. However, there's a treatment for the term 'media' that is much more vast than the one conveyed by common usage of the term, an expansive conceptualization that is useful in discussions about Reality.

In this line of thinking, media are the things that surround you – the objects, creatures and spaces that shape the story of your life. That is, by media you can refer not only to communication technologies like print, television, the Internet, or the phonetic alphabet, but indeed to everything else. Because what is a medium if not a means to communicate – to interact – with Reality? If the telephone gave people a new way to communicate with one another, the bicycle offered a new way to ‘communicate’ with the ground. In other words, media is that which – by means of existing – enables activity and behavior. Media are “aspects of Reality” that deliver a distinct experience upon engagement, the experience of interacting with that medium, a condition met equally by an animated GIF and a giraffe.

This is precisely why products work as ‘vessels’ for experience delivery. Like everything else, products are media. Media can be physical, mental, or digital. It is the food in your pantry, the clothes in your closet, and the things in your phone. It is the people you know and the buildings in your city, the everyday things of Norman and the forms of Plato, the world around us and the one inside your head. The nature of media as a source of experience gives its semantic expansion only one natural end: To encompass everything that can be experienced.)) Essay / Ways and Means to Deliver Experiences

It is with this understanding that you can appreciate new media as a critical element in human narratives. It is critical because our core narratives — that is, the story of humankind, the story of our community, that of our family, and our individual lifestory — are all epics in which new media is desired, discovered, dominated, and domesticated.

New media is valuable because it lets stories develop by providing an escape from soul-crushing monotony. Because no matter how perfect, an unchanging routine becomes unsustainable after enough repetitions. It's as if replaying an experience made it lose meaning, each repetition rendering it merely into "something that happens", slowly eroding any feeling of agency or control you may have. By unlocking new experiences, new media gives people the chance to add further color and spice to life. You could say this is what new media is about – the crystallization of the hoped-for, the worked-for, and the unexpected. It’s a device to continue our stories.

New Media embodies Progress

Talking about novelty asks for a frame of reference. For instance, we can discuss new media in the context of our individual lives. Have you ever taken a moment to consider how the things you own and use have changed? It's never a bad moment. As if molting old shells, people periodically shed and adopt new media through life. Do you remember the first time you rode a bike? Your first experience using a credit card? Your first mobile phone? We spend our lives discovering media, adopting it and learning to engage it in new ways.

From infancy to adolescence, to adulthood and on to seniority, the media we seek marks our passage through life's stages. We go from the pacifier, to the toys, to the books, to the dance floors, to the suits, and on to the funeral casket. Life is the story of our struggle to surround ourselves with the media we think we deserve and that gives meaning to our lives. It's an epic that weaves together our journeys to meet the people, places, and artifacts that make us feel comfort, enjoyment, and delight, including our soulmates, homes, and children.

A similar dynamic can be observed from afar. Societies as a whole, too, periodically upgrade their media stock with newer forms. One way to think about this media stock is in terms of different "sets"; consider for example "basic infrastructure", "means of transport", "consumer products", or "communication technologies". The media in these sets is constantly iterated upon, on occasion being superseded by completely new forms. These new forms become the fresh exoskeletons, nervous systems, and interfaces that allow societies to communicate better with the world and with themselves. Older forms evolve to fit the historical context better, an evolution done in the spirit of enabling a better life-experience for humankind. Because what is technological progress for if not to make life more bearable? And why bear with life if we cannot make it meaningful and enjoyable?

New Media has to be produced

Having established the appeal and need for new media in human narratives, we can touch on the top-level approaches available to produce it. In brief, new media can be either discovered, imagined, or synthesized. From this perspective, all media falls into one of two categories:

- Anthropogenic Form: Forms that come about as a consequence of human behavior, broadly construed to include behavior that happens inside the mind.

- Non-anthropogenic Form: Forms that occur independently of human behavior.

As discussed in Mediated Engagement, the world of media is the world of form. Anthropogenic form includes any media that could be considered synthetic, man-made, or artificial; it includes products, tools, prepared foods, songs, film, electronics, containers, software, roads, buildings, vehicles, and other such things.

Non-anthropogenic form is what people would colloquially call "natural" [in fairness, everything that "happens" is technically natural]; it includes terrain and its features (e.g., mountains, valleys), celestial objects (e.g., stars, planets), inorganic forms (e.g., water, minerals), and most biological forms (e.g., plants, animals, microorganisms). A brief overview of how these forms are produced is shared below.

I. DISCOVERING NEW FORM

The first approach to producing new media is discovering new forms already available in the environment (e.g., foodstuffs, objects/materials, lifeforms). As of the twentieth century (20th), however, every reasonably accessible corner of the earth has been explored and documented, making the discovery of new form via simple face-to-face encounters very rare. That is why, with the help of mediating artifacts, we have taken our exploration of reality to new frontiers. Using increasingly sophisticated technologies, we have slowly extended our senses into three new depths:

The depths of the ocean. At more than 1.8 kilometers (1.1 miles) under sea level, the deep seas are ostensibly the planet's last unexplored frontier. Long believed to be a barren wasteland, our progress in sea exploration has shown that the depths of oceans house the largest collection of undiscovered earthly forms. A combination of crushing pressure, absence of light, and an infinite heat-sink, however, make the deep sea a complicated environment to explore. The earliest ‘mediated’ visit to these depths was recorded in 1521, when Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan’s attempted to measure the depth of the Pacific Ocean with a 2,400-foot (~730 meters) weighted line that didn't touch bottom. Today, deep water exploration uses robotic submersibles that can be operated from ships in the surface.

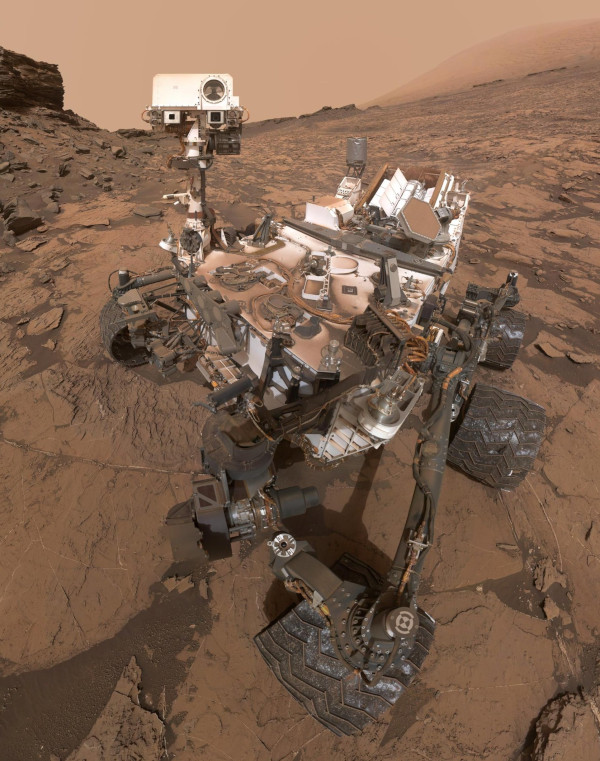

The vastness of space. People’s exploration of the skies began by contemplating celestial forms with the naked eye. But contemplating forms is seldom enough for humankind, so we’ve taken steps to get ever closer to them using artifacts like telescopes, rockets, and spaceships. Mediated expeditions into space started in 1957 with the launch of the USSR’s Sputnik 1 and 2 into Earth’s low orbit. Visits to the Moon began in 1959 with the Soviet probes Luna 1/2/3 and the American Pioneer 4, efforts that led to the landmark Apollo missions in the 1960s and culminated with Apollo 11’s groundbreaking manned lunar landing. Our neighbor Mars has been another popular destination, with 15 artifacts visiting the planet since 1970, two of which are still in operation. As of 2020, we have paid a mediated visit to practically every major feature in the solar system. As the hope of finding new planetary homes and enigmatic alien forms compel us to intensify our exploration, these efforts are sure to be just the beginning.

NASA's Curiosity rover landed on Mars in 2012 and is still in operation as of 2020. (Source: NASA/JPL-Caltech)

NASA's Curiosity rover landed on Mars in 2012 and is still in operation as of 2020. (Source: NASA/JPL-Caltech)The realm of the microscopic. The last depths remaining to explore lie not around us, but rather within us and within the forms we already know. What does our form consist of? What is form? What is it made of? The naked eye can only see so much. The earliest accounts of “the worlds within” come from the ancient Greece (5th century BCE) and it took centuries before English chemist John Dalton refined these ideas into his atomic theory (1803 -1809). Dalton’s theoretical account had to be revised a few decades later when physicist J. J. Thompson (also English) discovered the electron in 1897, thus revealing the existence of forms smaller than the atom. This led to the discovery of the proton at the turn of the century (1919), quickly followed by the discovery of the neutron (1932). A different but ultimately related narrative is our discovery of microscopic biological forms, including the ones that constitute our bodies. This search led to the groundbreaking Human Genome Project (1990-2003), a 13-year effort to map the sequence of genes every human being is marvelously codified into. A similarly ambitious expedition, the Earth Microbiome Project (started in 2010), is currently attempting to map the wealth of microbial communities across the globe.

II. IMAGINING NEW FORM

Human imagination offers a safe place to conceive of new forms and engage them as we please. In a world where serious exploration came with significant risks to life and limb, imaginary forms must have been especially valuable. Since time immemorial, people have imagined entities, creatures, technologies, and places to serve a variety of purposes. Some of these "mental forms" were used to deliver experiential relief in the form of protection, guidance, and spiritual support. Others offered hope for good health and fortune. Others were simply conceived to deliver amusement, fascination, or a healthy dose of safe horror.

Eventually, collectively valuable forms acquired cultural relevance. Important mental forms were deemed worthy of representation onto physical media (e.g., through markings, engravings, sculpture, metalwork) that provided a tangible vehicle for engagement. Some forms became deities which could be engaged through prayer and which engaged back — in experience — through natural phenomena and life events. The richness of ancient mythologies can give us an idea of just how diverse these forms were. These "religious forms" tied people together by collective worship, a behavior that integrated rituals as well as oral and written tradition that preserved and spread the forms further. These colorful collections of gods eventually collapsed into the modern array of unitary omnipotent gods, their last possible iteration, forms sculpted by the same forces that drive the evolution of all other anthropogenic forms.

The role of imagination as a source of new form retains its relevance today. Considering we now have the technologies to actually synthesize many of these forms, the role of imagination may even be more consequential than ever. The minotaurs, sirens, and genies of the past have given way to fantasies of space colonization, artificial intelligences, and simulations of reality. From Julius Verne and H. G. Wells to Aldous Huxley and Isaac Asimov, the modern tradition of science fiction continues to feed our conception of futures we consider possible, plausible, and preferable. These and other frontier notions now serve as a spiritual road map for the development of new media.

III. SYNTHESIZING NEW FORM

The last approach to produce new media is by synthesis. Synthesis refers to any action that modifies the environment in a way that produces new form; in other words, when a person uses existing form to produce something new, they are performing synthesis. Forms that don't happen without human intervention are commonly referred to as synthetic, artificial, or man-made. Synthesizing new form is humankind's signature ability, an activity for which our species is uniquely skilled and motivated. As human beings, we are form that produces new form, we are __homo faber. It‘s hard to make enough emphasis on how transcendental this is: Living organisms are replicating forms, forms with the ability to produce copies of themselves; but humankind takes this behavior one step further by also synthesizing forms different__ than itself and providing means for their replication.

The rise of human-made media is, in essence, the rise of replicating non-biological forms.

As discussed in Mediated Engagement, all human activity/engagement is context-specific. By extension, the motives a person may have to synthesize new form are also context-specific and much too-varied to attempt enumeration. If you believe that the spirit of human behavior is to improve present and/or future experience, you could at least say that, at a very high level, all synthesis happens with the same goal in mind, regardless of who ends up benefitting from the end-product (e.g., ourselves, others).

One last observation to share before discussing methods of synthesis is that new form can only be synthesized using existing form [might be in connection with the classical notion of conservation of mass]. This leaves us with two possible methods to synthesize form:

Iterating existing form. Every medium is in itself a ‘concept’ that can be iterated upon to produce new form. Prominent examples of iterative man-made media are consumer products, like automobiles, digital interfaces, and consumer electronics. Changes in the form of any existing medium will produce a new medium by changing its identity. In other words, a new medium is that which has identity of its own.

- The identity of a medium changes when you change its form.

Changing the form of a medium also inevitably changes the experience it delivers upon engagement.

- Forms with different identity offer different experiences.Forms with different identity offer different experiences.

A change in form may or may not result in changes to the medium's affordances. That is, change in a medium's form doesn't necessarily alter its function.

- Altering a medium's form may alter afforded behavior.

Encapsulating existing form. We can think of the process of bringing together existing forms to create new media as some sort of ‘encapsulation’. Encapsulation can happen in a literal or in an abstract sense. Literal encapsulation refers to cases where the encapsulated form becomes a palpable new thing. This literal encapsulation refers to something that happens "before your eyes" when multiple forms aggregate into a new, unitary, and perceptually continuous medium. When this happens, the resulting medium acquires — in your mind — an identity of its own that is different from the identities of its constituent forms.

- Forms can be encapsulated in a literal sense to create a new medium.

Existing forms can also become a new medium by working together in concert, without direct structural fusion/aggregation. You can think of it as an integration that is functional rather than formal. In this integration, the functions and affordances of the aggregated forms become coupled, allowing the component forms to offer the functionality of the forms they are connected with. Arrangements of this kind are traditionally known as “systems”, encapsulations of form that happen not before our eyes, but "before our minds".

- New media can be created by the abstract encapsulation of forms into systems.

Systems are encapsulations of interacting form that allow people to communicate and engage with the world in ways previously unavailable. In different words, systems are media, aspects of Reality worthy of an identity of their own. The notion of ‘mediated engagement’ makes the power of systems easier to understand:

The most consequential forms of mediated engagement happen by forming 'chains' of mediation. You can see these chains at work in the systems that sustain life and order across the globe, be them political (e.g., representative forms of government), economical (e.g., division of labor, supply chains), or technological (e.g., machines, software, the Internet). We can think of every chain of mediation as a form of technology.)) Essay / An Enactivist Account of Human Experience and Behavior

Every system constitutes a chain of mediation, a pattern of engagement/interaction between forms. In a chain of mediation, the function of two or more forms is connected to obtain an additive and/or synergistic effect (e.g., engaging an object remotely), thus allowing systems to exhibit behaviors greater than the sum of the parts.

The Case of Representational Media

There is one last approach to produce new media that deserves a special mention and that is representation. In section above we explored how new form can be produced by synthesis – the modification and/or encapsulation of existing form. Representation refers to a special case of synthesis where existing form is modified to resemble other forms. Books, music, painting, photography, film, software, and their derivatives are all representational media.

Since the late twentieth century, the world of representational media became all the more relevant when we started representing forms digitally, that is, using digits and numerical structures. Understanding this digital breed of media is essential to make sense of the world in the new millennium. The impact of digital media on the order of things social, political, and economical is comparable in magnitude to the introduction of the printed word [if not bigger!]. We shall discuss representational media in a different entry because we are already at 4,000 words here. Suffice it to say that it is truly magical; representational media doesn’t fill any “hard” human need (in the traditional conception of the word) yet we produce it abundantly. Understanding why we produce representational media can shed further light as to why people produce media in the first place.

The Spice Must Flow

In the twenty-first century, media is produced not only to sustain life but to sustain life narratives. Every human life is a story worthy of embellishment, a felt journey that asks for cadence, structure, and change. But stories are fragile, they go off-rails easily and are very prone to monotony. Writing and enacting a compelling life story demands a level of supervision and execution that is not easy to deliver. Living life as a human being demands putting together three roles long disaggregated by cinema – those of director, actor, and spectator. It’s an uncanny triple duty that not everyone is ready, let alone willing, to take on. The promise of modern media is to take some of this directorial burden off people’s shoulders. Modern media delivers plot and setting by shaping our environment and giving us things to hope for and work for. Its aim is to put us in control over what makes it into the picture, to give us a say over the content of our lives.

In a world with 7.8 billion people and equally numerous narratives to be embellished, the global need for media is voracious. Like the spice trade in the past, the design, production, and distribution of modern media keeps our economies vibrant and fills the world's roads, seas, and airwaves with activity. Using it and consuming it fills our own days and weeks with color. Today, media is produced in cycles to satisfy our collective demand for change and novelty. Cars and gadgets are refreshed every year. Fashion changes naturally with the seasons and then again. News media is produced by the hour. We produce new media because change is at the center of every narrative, because change is what makes a story worth telling.

As noble in spirit as this mass media enterprise could be, it brings to bear a series of unintended consequences:

- Mass media turns people into consumers: By filling our surroundings with everything we may possibly want, we remove incentives to do things on our own.

- New media is inertial and self-propelling: Once a new iteration of an existing form is released, we are incentivized to upgrade lest we submit ourselves to a “lesser experience”.

- New media changes personal and collective behaviors in unforeseen ways: The societal effects of new forms are hard to estimate before they are released into the wild.

But the modern mass media dynamic is hard to tame because, for better or worse, we are hard-wired to appreciate novelty. Humankind’s fascination with new media is fueled by the very mechanisms that gave us an edge over prey and predator: We are naturally attracted to change because changes in our environment are salient in our experience. But when people become fully reliant on mass media to furnish and animate the sequence of their lives, they surrender directorial power to the individuals, organizations, and systems in charge of pumping that media into their physical and digital environments. When novelty becomes an end in itself, new media becomes the protagonist and we become the means for it to prosper. And it should be people the ones lending meaning and purpose to media, not the other way around.

✎ Connection to