The Monetization of Value

The prominence and visibility of products and services in the modern economy obscures the true role of the firm. It was discussed in Reducing Friction and Experiential Rewards that firms deliver value through products and services that reduce friction and/or media that produce experiential reward, ‘offerings’ with the function of improving people's experience. In and of itself, the role of the firm is not to provide products or services but to provide experiences that are better than the ones available in its absence. In this sense, the modern firm can be interpreted as a ‘provider’ of experiences.

Indeed, commercial firms act as experience providers not only for their customers but also for the rest of the people involved in their operation. This becomes visible if you consider that the tasks and activities necessary to deliver the value proposition to the firm's customers are directly experienced by employees. A similar argument can be made of people acting as suppliers and contractors to the firm – they directly experience the activities they perform to assist and enable their clients' operations.

Notice, however, that the experiences that a firm delegates to its employees, contractors, and suppliers are not like the ones it provides to customers. They are burdensome experiences in most cases, they are ‘experiential costs’. For taking on these burdens, employees are compensated with money which they can, in turn, spend to improve their own experience. From an experiential point of view, we can see the operation of any firm for what it really is: A dynamic in which participants take part with the goal of improving their individual experience.

Experiential Value can be Monetized

The process of turning experiential value into its monetary equivalent is called ‘monetization’. Akin to what metabolism is to living organisms, monetization is vital for the modern firm because it enables the crucial transformation that makes its operation sustainable: It transforms the value delivered to the customer into value for the people making it happen. This transformation involves money.

We can think of money as a store of experiential value, ‘credits’ that people earn by delivering value to others. When you pay for a product or service, you are trading money for an experiential benefit. In this act, you are choosing to incur a monetary cost instead of bearing the experiential cost associated with obtaining the benefit yourself. Since delivering experiential benefits usually involves taking on experiential costs, using money amounts to trading already-lived experiential costs for present or future experiential benefit.

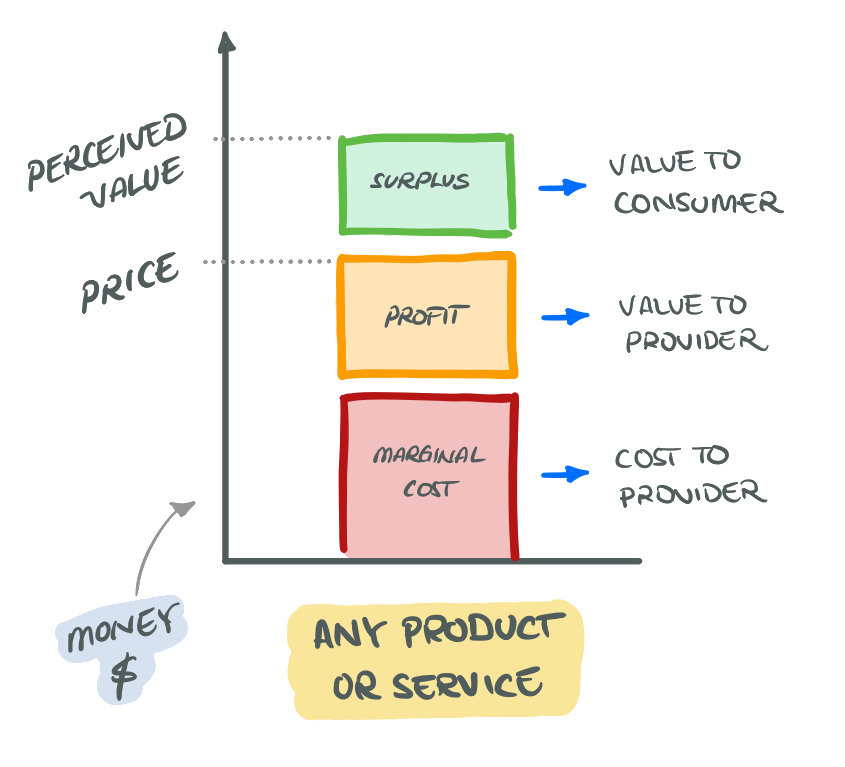

To facilitate monetization, firms usually set ‘prices’ on their experiential offerings. Pricing is the act of staking a monetary claim to the value that is either delivered or enabled by the firm, a price being the level at which the claim is established:

The value of an experiential offering is usually split between its consumer and the provider.

The value of an experiential offering is usually split between its consumer and the provider.Prices help people perform their assessments of value and decide whether the trade they are entering is worthwhile. People only pay for experiences when they believe it is experientially favorable for them to do so, even if only marginally.

As discussed in Experiential Value, value is in the eye of the beholder. As such, when a firm sets a price it is exercising an understanding of the value it delivers to the customer. Firms naturally make pricing decisions considering their target customer, the leverage they have in the transaction, and the amount of business they expect to bring in at each price level. With so many variables at hand, pricing an experience can be challenging. Setting too high a price can keep away potential customers, leaving the firm with unrealized business. Pricing the experience too low can put the viability of the business at risk.

Ideally, the resources obtained by the firm through monetization are enough to cover the costs incurred in delivering its value proposition. However, firms don't measure their success by their ability to cover costs but by the amount they are able to monetize above the true cost of providing the experience. The issue of how the value of an experiential offering is split between the firm and the customer is, of course, a question of leverage.

Prices are determined by Value and Leverage

When a customer accepts a price above cost, they are not only indicating that they perceive the value of the experiential offering to be of at least that level; they are also acknowledging the leverage of the firm in setting the price. The leverage a firm has over the price of an experiential offering increases with its value proposition and the degree of control the firm exerts over it. The higher the leverage, the more value the firm is able to claim for itself. A firm has maximum leverage when they are the only way to access a given experience.

High-leverage situations give firms the ability to use ‘value-based’ pricing – the practice of setting prices commensurate to the value delivered or enabled to the customer. Not surprisingly, firms that price based on value command higher profit margins. Value-based pricing is commonly used in well-differentiated experiences with a unique value proposition. Think, for example, of experiences that require high levels of technical sophistication, skill, and/or artistic ability like those in the worlds of high art, higher education, designer furniture, and specialty healthcare.

Commoditization: Losing Leverage

Successfully bringing a new experience to the market naturally attracts competition. This is especially true when the firm behind it appears to be commanding high margins. Not only are would-be competitors lured by the potential of high profits, they are also attracted by the opportunity of avoiding the experiential costs associated with validating a completely new experience in the market.

The entry of rival firms to the market often results in a loss of differentiation in the experiences they provide, a process known as commoditization. Commoditization is undesired by firms because offering fully undifferentiated products leads to perfect competition, a scenario characterized by price wars and low profit margins.

From a societal point of view, however, competition and commoditization are positive developments. Competition increases capacity and makes the experience more accessible to everyone. On the other hand, commoditization decreases the leverage that any given firm has over pricing, allowing the public to pay a price closer to the actual cost of the experience. At the limit, commoditization renders firms ‘fungible’, meaning customers can switch providers and obtain a comparable experience without any significant trade-offs. At this point, the experience is considered a commodity.

Pricing without Leverage

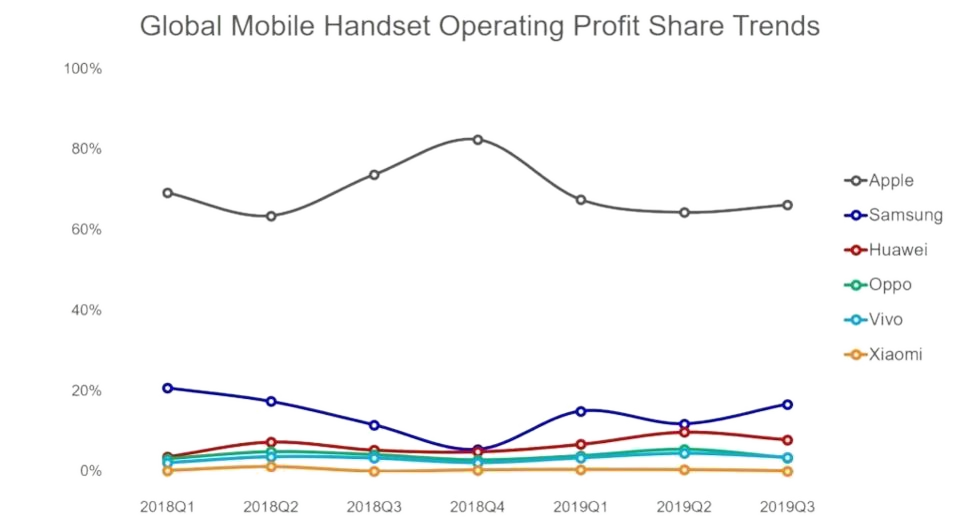

When firms lose their pricing leverage, they can no longer price experiences based on their value. Instead, they are left with ‘cost-based’ pricing, a situation where the price is based on the costs effectively incurred in providing the experience. Compared to value-based pricing, cost-based pricing severely limits the margins that can be earned as profit. Consider, for example, the well-known case of Apple's dominance of the smartphone industry's profits. From Counterpoint Research:

Apple dominated headset manufacturer profits in 2019.

Apple dominated headset manufacturer profits in 2019.In 2019, Apple was responsible for less than 20% of smartphone shipments, yet it claimed over 60% of the profits generated by all the major handset manufacturers. It is not that Android headset manufacturers are not delivering value to their customers, but that they have little leverage over how they price their products because the experiences they provide are all too similar. In contrast, the iPhone and iOS deliver a well-differentiated smartphone experience, one that people can only access through Apple. This leverage allows the company to claim a much larger stake in the value it delivers to its customers than its competitors.

Differentiation: Fighting Commoditization

At the core of commoditization is the loss of differentiation. It follows that, to resist commoditization, firms implement strategies to make sure their experiential offerings stay differentiated in the market.

There are two ways in which a product or service can be differentiated. The first type of differentiation is tied to the degree of experiential relief or reward it offers. For instance, let's think of a water bottle. The degree of experiential relief that a water bottle offers is tied to its capacity, i.e., a bigger water bottle is capable of ‘quenching more thirst’ than a small one. We say that these two bottles are vertically differentiated by performance. Other examples of vertically differentiated experiences are:

- Getting two-day shipping vs. five-day shipping when you purchase an item online.

- Being able to use your phone for a full day on a single charge vs. being able to use it for only 8 hours.

- Taking a direct flight to New York City vs. taking one with layovers.

When it comes to products, vertical differentiation is connected to the product's performance (e.g., efficiency, processing speed). When we talk about services, it is about service level (e.g., response times, downtime). The result is that, if a set of vertically differentiated experiences were offered at the same price, all customers would rank them in the same way and everyone would choose to buy the same one.

The second type of differentiation is tied to the ‘means of achieving’ a given experiential relief or reward. Let's return to our water bottle example. The experience offered by a water bottle is quenching thirst. But what if instead of using a water bottle we used a water fountain? We say that the experiences of quenching your thirst using a water bottle and using a water fountain for the same end are horizontally differentiated. Other examples of horizontally differentiated experiences are:

- Listening to a music album through an online streaming service vs. listening to it on vinyl.

- Getting a workout by attending a yoga class vs. attending a kick-boxing session.

- Having dinner at a Japanese restaurant vs. having it at a Brazilian steakhouse.

Horizontal differentiation is connected to the qualitative aspects of the experience. It is not about function, but about form. When it comes to products, it involves aspects like colors, flavors, and shapes. On the services side, it is about the felt aspects of the interactions with the service provider (e.g., ambiance) and the way the interactions take place (e.g., on the phone vs. e-mail). The result is that, if a set of horizontally differentiated experiences were offered in the market at the same price, there would be no agreement as to which experience offers more value and customers would purchase according to their tastes and preferences.

In practice, it is common for experiential offerings to be differentiated both, vertically and horizontally. This yields positive outcomes from a societal standpoint because it fills markets with experiential offerings that suit every taste. Working in tandem, commoditization and differentiation minimize how much people have to compromise to make the most out of daily life.

Moats: Fighting Competition

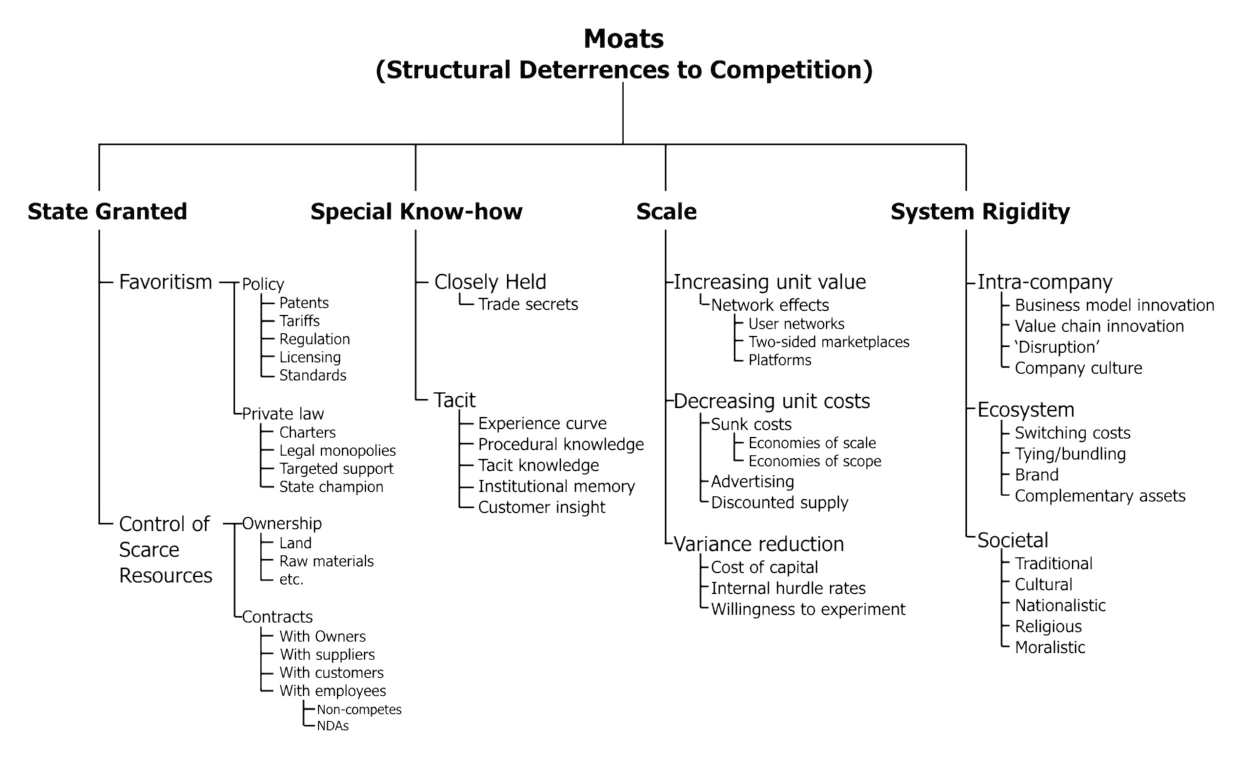

Differentiation is not the only way in which firms protect their pricing leverage. Firms can also deter competition by building ‘moats’. Just like medieval moats gave castles some degree of protection, moats in the business sense are quite literally situations that keep a firm's value proposition out of reach from competitors. Here are some popular examples of moats:

- The exclusivity agreements that Ticketmaster keeps with concert venues.

- The network effects around social networks like Facebook and payment networks like Visa and Mastercard.

- The economies of scale achieved in chip manufacturing by Intel or the ones achieved by Amazon in order fulfillment.

- The rights held by Disney over media franchises like Star Wars and Marvel.

A firm has a moat around an experience when it has structural advantages that make it hard (e.g., technically, economically) for competing firms to offer a similar value proposition. Moats can also take the form of legal or physical obstacles that keep rival firms from offering comparable experiences (e.g., exclusivity agreements, intellectual property, and real property). Jerry Neumann, investor and teacher of entrepreneurship at Columbia University's School of Engineering, summarized moats neatly in a taxonomy posted on his blog:

A taxonomy of moats by Jerry Neumann.

A taxonomy of moats by Jerry Neumann.

Futureproofing the Business

As experience providers, firms take on two additional responsibilities. A first duty is to ‘maintain’ the experiences they enable. The rationale for maintaining an experience is simple: The value proposition of an experiential offering can erode with time, especially when the context and expectations of customers evolve. Maintenance is about protecting this value proposition, sometimes even expanding it. Firms accomplish this through activities collectively known as ‘product management’.

But maintenance is not enough. Firms also have to think about the future and imagine new experiences. In a business context, the art and practice of developing new experiences is known as ‘innovation’. Despite it being a much-hyped word, it remains the only sure way for firms to escape the natural progression towards commoditization because it allows firms to offer value propositions that are, by definition, unique and differentiated.

The tales of firms that lost their dominance like those of Barnes & Noble, Nokia, and MySpace are a fading reminder that maintenance and innovation are crucial for the long term viability of any enterprise. Firms that abdicate these responsibilities are destined to be superseded by others that embrace them.

✎ Connection to

Key / The Reproduction of Money

Key / A Whole Cultural Way of Relating