The Adaptive Role of Cultural Artifacts

A Mysterious Behavior

In the southernmost corner of the Americas, a place known as the Patagonia, there is an ancient cave where the walls can speak. There, stamped over the surface, one can easily distinguish the familiar contour of human hands, hundreds of them, carefully stenciled over the rock. The hollowed out bones found at the site suggest the art was spray-painted. The reddish pigments appear to have been sourced from ores available in the cave. Taken out of context, the artwork on display at La Cueva de Las Manos (Spanish for "Cave of the Hands") could pass as a cute community project. For eyes habituated to infinity rooms and 4K video, it may even seem unimpressive. But for those with minds prone to wonder, these walls offer a connection that contemporary media cannot: If you were to fit your hand within the negative space in any of these prints, you'd be placing it on the exact same place where another human, some 10,000 years ago, placed theirs. Within its wavy contours, each print offers a window into the very moment it was produced, and with it, an opportunity to connect with an ancient individual whose relationship with Reality was so utterly different than yours. This isn't a feeling offered by naked rock. If the prints were not materially there, this experience wouldn't be possible.

The main wall at La Cueva de Las Manos archeological site (Mariano Cecowski, Wikimedia Commons).

The main wall at La Cueva de Las Manos archeological site (Mariano Cecowski, Wikimedia Commons).The archeological significance of La Cueva cannot be understated, the site is more than a memorial to the people who called its walls home: Located as far as one can possibly travel by land from the African continent (assuming the Bering Strait was used to cross into the Americas), its stencils are a unique monument to humanity's drive to reach new frontiers. The site, however, is not without precedent; similar imagery is on display at a handful of archaeological sites, thousands of years older, located across Europe and Asia. Together, the artwork at these locations constitutes some of the earliest evidence of a mysterious human behavior. Very generally, we call it representation.

For thousands of years, peoples across the globe have produced objects that resemble other things, objects made in the likeness of animals, people, celestial bodies, and countless other forms. We call these objects representational artifacts because they embody more than their immediate form, they capture and re-present the essence of something else. Some are self-evident, like the figurine of a dog, the carving of a mother, the depiction of the sun. Others have meanings that continue to elude us. And yet, uniting them all is a common driving force that defies simple articulation. What is the significance of representation? What do representational artifacts do for us? The answers seem essential to understand the modern media landscape.

Adaptation: Seeking Fitness

In the nineteenth century (1800s), the groundbreaking observations by Charles Darwin fundamentally altered the narrative as to how our kind came about. Biological forms, he found, change gradually through time in a process driven by environmental change. The story goes like this: A changing environment presents new problems that exert pressures on the organisms that live in it. The life forms respond by finding solutions to the problems posed by the changing environment. If they adapt successfully, they keep biological balance, they reproduce and their form survives another round. If they fail, the opposite happens; biological needs cannot be met and the likelihood their form will live on is reduced by malnutrition, injury, or death. Adaptation, in this sense, is the process by which a form reaches viability and harmony with its environment. When a form—here, an organism—is well adapted to its environment, we say it exhibits fitness, a relation of adequacy and mutual acceptability between the form and the environment. It is a two-way street: An organism 'fits' an environment if it can make a home out of it; likewise, an environment fits an organism if it provides what the organism needs. In this way, fitness refers to the ability of the organism to survive and thrive in an environment, while adaptation is the process through which the organism achieves said fitness.

In the public imagination, discussing adaptation quickly brings to mind imagery of creatures developing wings, claws, teeth, fur, shells, and the countless other features of contemporary animal forms. Adaptations of this kind—those manifesting as a change in the form of an organism— are typically referred to as morphological adaptations (also structural, physiological, or anatomical). Among other things, they include the development of protective layers (e.g., exoskeletons), limbs (e.g., legs), bodily tools (e.g., pincers), and internal organs (e.g., hearts, guts). The form of every organism is a living record of morphological adaptations that have worked in the past, a developmental morphosis that can be understood as the cumulative result of anatomical changes collected through generations. Thanks to its visual tangibility, morphological change captured people's imaginations and became in our minds synonymous with evolution. But Darwin's work did not dwell exclusively in morphology, he also studied the development of "habits", or adaptations of a behavioral nature. The logic is the same: When we ask if a physiological trait is adaptive, we are asking if it is 'well-suited' to the demands exerted by the environment; in a similar way, we say a behavior is adaptive if it contributes to the organism's well-being by achieving overall fitness with the environment.

While it may not carry the visual appeal of an evolving form, producing and systematizing adaptive behavior is crucial to the viability of living organisms. In fact, given that morphology is largely driven by heredity (i.e., it is genetically determined), producing adaptive behavior is the sole strategy available to an individual organism to survive drastic environmental changes. Take, for instance, the sudden appearance of a predator. Upon encountering a cheetah, you could hardly expect an antelope to develop claws to fight it or camouflage to hide from it. The only option to solve the problem presented by its immediate environment is to run... as fast as it can! By running faster than its predators, the antelope will be viable and exhibit fitness without the need to develop structural adaptations to that effect.

Seeking Fitness: Creating Form

What the case of the antelope tells us is that a living organism can adapt to its environment by producing behaviors that make up fully or partially for missing physical adaptations. That is, morphology and behavior can be 'exchanged' to some degree; there is an equivalence in their effectiveness at making an organism belong in its environment. A different creature makes this trade-off more concrete: Having never developed a shell for itself, the hermit crab takes shelter in rigid objects with suitable cavities, usually empty shells left behind by snails and other mollusks after death. By leveraging existing shells, the hermit crab protects itself from predators and achieves environmental fitness without having to grow one for itself. This peculiar behavior carries an important revelation: For an organism, the adaptive value of leveraging external forms is equivalent to that of developing comparable forms onto itself. When an organism leverages forms already existing in the environment, it gains independence from the form bestowed to it by heredity, relying less on it to meet its needs. In other words, there is a dualism between morphology and behavior, between form and function; they speak to the same thing.

There is another peculiar behavior we can think of to appreciate this duality: The production of tools. Tool-making doesn't bridge the gap between form and function, it blurs it quite literally. It consists in the modification of external forms to produce artifacts, forms that aren't readily provided by nature. By producing artifacts, a creature comes as close as possible to ending its reliance on preexisting form to achieve ecological fitness. Tool-making puts a creature's destiny in its own hands, making it easier to adapt to a changing environment without undergoing dramatic physical transformation nor embracing the commitments that come with it. Why spend centuries growing claws or fangs when you can make weapons? Why grow hair or rough skin when you can make clothing?

The ability to create new form is known as synthesis, the king-maker of adaptive behaviors.

Humankind's unique mastery of synthesis has allowed it to thrive in essentially every climate and geography in the planet. Though other animals are known to use and produce functional objects and structures, human creations are unmatched in their scale, sophistication, and variety. Our faculty of synthesis gave us not only survival, it also gave relative stability to the human form across the ages. In "Descent of Man", Darwin himself discussed how the use of tools might have even reversed some of the structural adaptations developed by our ancestors:

"The free use of the arms and hands, partly the cause and partly the result of man's erect position, appears to have led in an indirect manner to other modifications of structure. The early male forefathers of man were, as previously stated, probably furnished with great canine teeth; but, as they gradually acquired the habit of using stones, clubs, or other weapons, for fighting with their enemies or rivals, they would use their jaws and teeth less and less. In this case, the jaws, together with the teeth, would become reduced in size, as we may feel almost sure from innumerable analogous cases." (p. 53)

Is Representation Adaptive?

It is within this context that I would like us to make sense of representation. Does representation constitute adaptive behavior? And if so, what is the adaptive value of it? Because it's easy to make sense of our ancestors spending time producing a spear, a hammer stone, or a sword, tools with evident value to survival; but what is the adaptive value of a carving, a marking, a painting, a jewel, an ornament, a tapestry, or a sculpture? How does producing any of these increase the fitness of anyone in their environment? The field of evolutionary psychology, an approach that studies the adaptive role of the psyche and behavioral patterns, offers a handful of hypotheses. In my estimation, the most convincing are the ones that highlight the role of representation in human cognition and human communication. Explaining the cognitive function is neurobiologist Semir Zeki (University College London), who compares the arts to an extension of the visual brain. Like the brain, he says, the arts are used to acquire information about the world. He argues the proposition at length in his 1999 book:

"[The function of the arts is] to represent the constant, lasting, essential and enduring features of objects, surfaces, faces, [and] situations (...) thus allow us to acquire knowledge not only about the particular object, or face, or condition represented on the canvas but to generalise from that to many other objects (...)" (pp. 9-10)

Cognitive accounts of representation are clear about the adaptive value it offers: When people create a representation of something, they are attempting to capture its likeness in a medium, a medium that in turn affords an opportunity to understand the represented elements better. These embodied representations allow the individual to artificially increase its familiarity with environmental hazards and elements of biological significance (e.g., food, water, minerals, shelter), a familiarity that then confers an advantage at the time of identifying threats and opportunities. The adaptive value of representation in terms of communication is a natural extension of this idea: If, like proposed above, early humans used representation to "know what to look for/to look out for", then it only made sense for them to use representation to share this knowledge with others. By using visual representations like markings and drawings, people could share the things they saw or expected to see for others to keep in mind. In this sense, representation is a device for sharing experience. Engaging in representation is to speak. Language itself is pure representation, the product of capturing elements of our experience phonetically and visually.

Representation is at the core of human communication because it consists in the externalization of the contents of our mind.

Cognitive accounts of representation are compelling because they succeed at articulating cold-hard adaptive value. They are joined in prominence by the sexual selection hypothesis, which sees representation as a mating device, and by the less convincing accounts that see representation as a mere epiphenomenon. Despite articulating adaptive value, however, cognitive accounts are not useful at the moment of explaining the rich variety of representational artifacts on record: As a study of the human hand, the artwork at La Cueva would seem excessive; nor does increasing familiarity with the shape of the human hand seem particularly important for survival. Plenty of ancient representational artifacts don't seem to be learning nor communication devices. If you asked me, many don’t even seem to be purely representational, but rather functional artifacts embellished through representation. If these objects tell us anything, it is that when people create artifacts, function and survival isn't everything and, if the non-functional component is adaptive, it is not immediately obvious how or why.

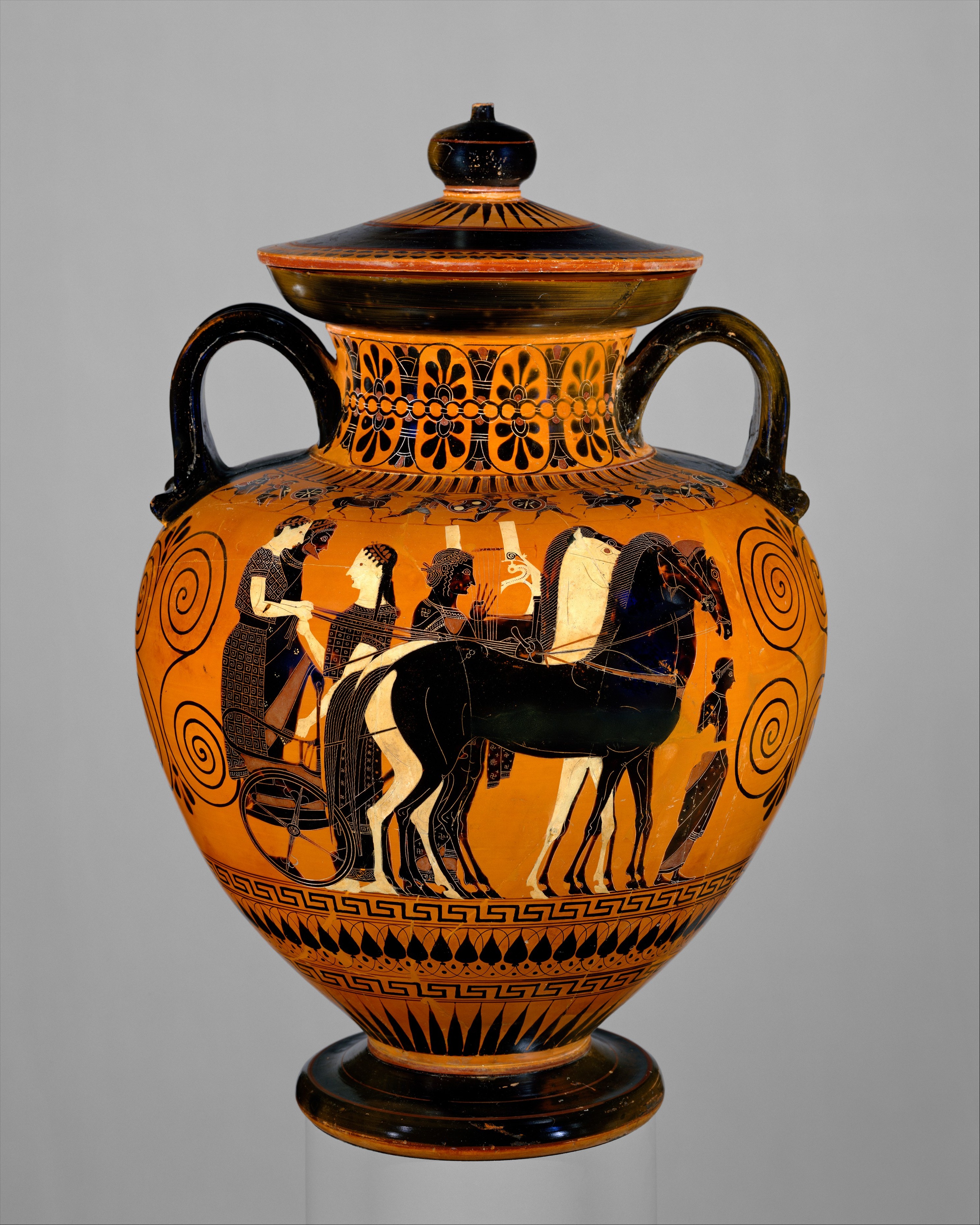

A wealth of ancient human artifacts incorporate functional and representational elements. Greek terracota neck-jar dated around 540 BC (The Metropolitan Museum of Art).

A wealth of ancient human artifacts incorporate functional and representational elements. Greek terracota neck-jar dated around 540 BC (The Metropolitan Museum of Art).

Producing Adaptive Behavior: Affectivity & Sensitivity

To make sense of representation we have to dig deeper into adaptive behavior. How, precisely, is it that our kind manages to produce adaptive behavior? In humans, adaptive behavior is largely driven by affectivity, an evolutionary development we share with the rest of the animal world. Affectivity is the ability to produce an affective response (also known simply as "affect"), an embodied, one-dimensional feeling that is elicited continuously as we live and interact with our environments; it ranges from pleasant to unpleasant in different intensities. When they arise, biological imbalances like thirst and hunger elicit negative affect, a coercive and unpleasant feeling that demands action take place to make it go away. Negative affects are also elicited when we interact with the environment in injurious ways, motivating corrective action that helps us stay out of harm's way. In contrast, positive affects are pleasant feelings that signal well-being; they arise from interactions with biologically significant elements and are our only positive indication that whatever is happening is good for us.

We can think of affectivity as an embodied fitness function, a felt sense of adequacy and harmony with our surroundings.

As a force that motivates adaptive behavior, affect is of great adaptive value. Although far from perfect, it is our "way of knowing" if something ought to be done; it rewards behavior that tends to be adaptive while punishing behavior that tends to be maladaptive. I discussed human affect in Experiential Costs:

“Human affect (...) makes situations either costly to endure or rewarding to have. Affect, in a way, turns experience into a cost function, but one that you can feel. I want to stress that. A cost function takes some input and returns a value that somehow represents the cost or reward associated to the input. The higher the absolute value of it is, the higher the cost or the reward obtained. Similarly, the cost function of your experience takes the situation you are living as input but, instead of returning a value, it returns a feeling. This feeling, or affect, can be costly or rewarding to have and constitutes a primary appraisal of the experience you are having.”

The emergence of affective responsiveness in animals tells us that at some point during the evolution of biological forms, survival and behavior stopped being random processes. At this turning point, behavior stopped being merely "something that happens" to become something that happens towards something — behavior became a directed process. Instead of a random walk in which only a few roads led to survival, organisms started taking a safer route directing their behavior towards the objects of survival (e.g., food, water, minerals, shelter). But to get a sense of where these biologically significant elements might be found, affectivity is not enough: While it is certainly important for a creature to know whether it has found food or shelter, it is of equal or greater relevance they know when they encounter something that isn't food nor shelter but merely signals their proximity. To direct their behavior towards the objects of survival, organisms had to develop sensitivity to the objects and stimuli associated with them. Consider, for the sake of illustration, the sensitivity developed by spiders to mechanical vibrations: To the web-spinning spider, vibrations are intimately associated with feeding as they indicate a victim has been snared on the web and provide a sense of direction that can be used to locate the victim. Spiders also use vibrations to stay clear of predators, using hair-like structures on their legs to detect the chirp of hunting birds or the flapping wings of larger insects.

Sensitivity is the ability to respond to signals, to "see behind" what is presented to us.

Sensitivity is of great adaptive value because it lets organisms use objects and stimuli of indirect biological significance (positive or negative) to trigger and direct behavior. Developing sensitivity speaks of a higher adaptedness to the environment and a familiarity to the patterns in which it delivers bounty and hazard. Together with affectivity, it gives animal forms their distinctive liveliness and responsiveness.

Affectivity + Sensitivity = Symbolism

Affectivity and sensitivity are complex adaptive functions with cold-hard adaptive value: Together, they make anything we might encounter feel like a threat or an opportunity. To a thirsty traveler, they make the sound of a nearby stream feel comforting; to the sleeping homeowner, they make the sound of breaking glass feel distressing. By tinging everything that enters our experience through the senses with feeling, affectivity and sensitivity give us a formidable system for survival. From an experiential point of view, however, their transcendence is much greater. Thinking of them as fancy behavioral triggers would be grossly reductive. From an experiential point of view, affectivity and sensitivity produce something truly magical: They make things feel like other things. For us, the things that appear in our experience feel not only like threats/opportunities or things pleasant/unpleasant... they also feel like something else. If the sound of a stream is comforting, it's because it feels like water; if the sound of breaking glass feels distressing, it's because it feels like an intrusion. For us, forms of the human kind, everything feels like itself yet also like other things. In our minds, nothing exists in isolation, everything stands for something else.

In the human mind, every single thing is connected to something else because nothing is ever experienced in isolation.

Objects and stimuli become associated in our minds when they are felt/experienced at the same time. When objects appear concurrently in our immediate experience, affect tinges them with feeling, a feeling that binds them and commits them to our memory. After this happens, the objects become paired in our minds, by feeling, and any future encounter with one may invoke the others. When an object enters our immediate experience, it produces a feeling that calls forward moments and experiences that produced a similar feeling, reaching to the depths of our memory and pulling them into our mental presence.

The transcendence of affectivity is that it allows us to sort phenomena (e.g., objects and stimuli) by feeling.

Our mind associates every element that enters our experience by a likeness of feeling; every person, creature, and object; every emotion and sensation; every taste and every scent; every frequency and every voice; every event and every thought. In the stream of human experience, everything that appears becomes tinged with and related by feeling; every caress and every cut; every color, curve, and shape; everything, pleasant and unpleasant; every word — read, spoken or heard; everything, hot or cold; and everything — beautiful, shocking or repulsive. We relate roses with thorns, thorns with needles, and needles with pain. We connect the lightning with thunder and thunder with rain. In the mind, every experienced thing is tinged, related. Our memories, vast archives of elements tinged with and related by feeling.

The human mind deals in symbols — forms connected by a likeness of feeling.

For us, people, every single thing stands for something else, every thing feels like something else. Human sensitivity is symbolic in a unique way. We are affecto-symbolic creatures, creatures that experience affect and have symbolic sensitivity.

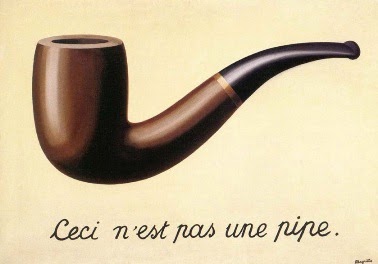

René Magritte's "The Treachery of Images"

René Magritte's "The Treachery of Images"

Biological Balance is not Enough

As Darwin theorized on the balance species achieved with their environment, a different but closely related equilibrium was being studied in France by fellow biologist Claude Bernard, decorated scientist and father of modern physiology. Using vivisections, controversial procedures performed on live animals, Bernard discovered the regulatory functions of the liver and the pancreas, findings that led him to appreciate the delicately balanced environments creatures maintained within themselves. In 1854, four years before the publication of Darwin's Origin of Species, Bernard started publishing the ideas that would develop into our modern understanding of homeostasis, the notion of internal physiological balance:

“The living body, though it has need of the surrounding environment, is nevertheless relatively independent of it. This independence which the organism has of its external environment, derives from the fact that in the living being, the tissues are in fact withdrawn from direct external influences and are protected by a veritable internal environment which is constituted, in particular, by the fluids circulating in the body.”

In Darwin and Bernard we find two alternative articulations of fitness: For Darwin, fitness was ecological, he saw creatures fitting their environments as puzzle pieces. Bernard, on the other hand, took a closer look at the creature; for him, fitness was physiological, the result of maintaining a stable internal environment or "milieu intérieur", as he termed it. The two views are complementary: Ecological fitness facilitates survival and continued survival, if anything, is evidence of sustained physiological balance.

Empirically, the fitness of biological forms manifests as ecological and physiological equilibrium.

As scientists do, Darwin and Bernard assessed fitness empirically, i.e., as external observers. From the point of view of an affective creature, however, these views mean little... when you are a feeling creature, the only guide to fitness is the way you feel. From an external point of view, fitness seems to be about survival and homeostasis; when you move the camera inside, however, fitness is about feeling adjusted and adequate. Feelings are hard to assess externally but from within, they can't be ignored. Inside, where everything feels like something —where feeling is all there is!— fitness is not reduced to maintaining biological balance, it is about finding a felt sense of harmony and mutual acceptability with the environment. Biological balance boils down to mitigating negative affects (e.g., eating when hungry, seeking warmth when cold), it’s about keeping your life bearable. But when you feel, the absence of negatives doesn't make a positive. In feeling beings like you and me, affectivity demands we be in positive territory. For us to feel adjusted we need to be in positive agreement with how we feel, with the things we do and the things that happen to us. To reach a felt sense of harmony we have to feel good with the things in our physical and mental presence, with the people, the objects, the images, and the activities around us and what they all signify.

When you are the creature, fitness is not evaluated empirically but affectively.

As anyone who has dealt with clinical depression will tell you, you cannot tell a person they are adequate, they have to feel it. Positive affects are, rather definitionally, feelings of agreement and adequacy, the only felt indication that we belong in our immediate environment. Delivering a steady flow of positively charged experiences makes life positively enjoyable and fit to live. More than an indicator of biological balance or imbalance, human affective responses are a true measure of agreement-disagreement with immediate experience.

Seeking Harmony: Creating Artifacts

The question lingers. How do we explain our rich history of representation? In my appreciation, the phenomenon/behavior of representation is humankind's response to the intense demands of its own affectivity and sensitivity. My argument is dialectical: A complex and changing environment demanded we develop systems to feel and survey our surroundings in order to survive. Now, these very systems demand we shape our surroundings in ways that make us feel not only safe, but positively stimulated; they demand we furnish a stabilizing and stimulating environment, one that assures continued sentience is not only guaranteed but worthwhile. We use synthesis and representation to create artifacts/objects/structures that serve this dual goal. I took a moment to discuss the significance of human synthesis in New Media:

“Synthesizing new form is humankind's signature ability, an activity for which our species is uniquely skilled and motivated. As human beings, we are form that produces new form, we are homo faber. (...) Living organisms are replicating forms, i.e., forms with the ability to produce copies of themselves; but humans take this behavior one step further by also synthesizing forms different than itself and providing means for their replication.”

In some artifacts we prioritize the function, in others we prioritize the form. We learned to appreciate function because it makes it easier to meet physiological needs; function confers artifacts a value that is utilitarian. We learned to appreciate form because it is the vessel of the function and provides a distinct feeling to it; even in the absence of practical function, form confers the artifact a value that is aesthetic. Our kind, the human kind, creates artifacts to facilitate life and to cope with life, artifacts to help it weather the extreme nature of the strange gift it was given, the gift of feeling it all and being aware of it. That is why it only made sense for ancient peoples to carve stones in the likeness of the beasts that gave them sustenance, to engrave their weapons and pottery with the warmth-giving sun, and to turn their walls into stenciled family portraits. Immersed in a world that may have seemed hostile and dull, representation offered our ancestors an opportunity to make the world kinder, a means to attune the environment, however so slightly, to meet their sensibilities.

The emergence of human synthesis marks the appearance of biological forms capable of willfully diverting adaptive pressures back on the environment.

For ages, humankind has used representation to surround itself with forms that make it feel adjusted. We use it to fill our spaces with character, with beauty, to keep in our presence the things we hold dear. We use it to comfort, to motivate and inspire. We use it to remember that which matters — our families, our memories, our hopes and our dreams. To memorialize the victories, the failures, and the stories that gave us origin. To remember, across lifetimes and generations, the experiences we aspire to repeat and not to repeat. I say it without a doubt, we use representation to enliven our days and embellish our lives. We use it to tell our stories and share them with others. To capture the moments that made us feel once for us to feel again. To remember how it feels like to experience joy or misery, pride or humiliation, horror or surprise, disgust or wanderlust. By surrounding ourselves with artifacts (representational and otherwise) we adapt the environment to us, helping us reach a feeling of adaptedness, familiarity, and complementarity.

Bread and Circus

To wind down our discussion, I would like to touch on the products of representation. To make the ideas presented here more tangible, I purposely framed this conversation around cultural artifacts. However, being representation first and foremost a behavior, its basic product is a performance. It’s only when this performance modifies existing form (e.g., via engraving, painting, writing, etc.) that a representational artifact is produced, a logic that extends to modern recording methods (e.g., photography, analog/digital sound recording). At this point it should be easy to appreciate the two products of representation, one that is ephemeral (i.e., performance) and one that persists through time (i.e., representational media). I shall discuss both in a future opportunity, but don’t let me obscure the topic any further: We’re talking about the stuff that makes up your reality, the one you are experiencing as you glide your eyes through these words. None of the things you have read here are things you aren’t already intimately familiar with. Discussing the crossroads of representation and media is discussing the experiences you enjoy every day: the sports, the news, the games, the books, the shows, the films, the stories, the photos, the music, the videos, the concerts, the gifs, the memes and their vessel venues and devices. These are the things we produce to smoothen our passage through life. You are no stranger to them, you know how they feel. You know the humbling feeling of euphoria and communion at the climax of a concert. The warm feeling of comfort of a happy ending. The entrancing feeling and resonance of beholding beauty in sight or mind. Feelings like these deserve appreciation. This is reality hugging you, lifting you, telling you everything is ok, telling you it’s all worth it.

Representation has value because it captures the feelings that make conscious existence worthwhile, feelings we now distribute wholesale on shelves, stages, and screens. Not surprisingly do we go through all the trouble. As other value-producing activities, representation went from personal endeavor to specialized craft to organized activity directed by the profit motive. For a long time now, we have slowly delegated the creation and supply of cultural artifacts to the mass media enterprise. The crucial role of technology in this larger dynamic will be a future discussion. The mass media enterprise of the 21st century is quite an achievement, a force that produces and distributes the stories, feelings, and changing imagery we need to stay afloat. Today, our unwithering appetite for entertainment and stimulation is served by content that flows directly into our homes and pockets through wires and airwaves. The selection is virtually unlimited, every sensibility spoken to, every taste catered to. But whether this is a sensible arrangement is still to be seen. Market forces have made of representational media another commodity to be produced, used, discarded, and forgotten, mass-produced replacements for the lives we are too afraid, too poor, or too busy to produce ourselves. The stories no longer bear any connection to our lives, their transcendence no greater than a microwave dinner. Because the logic of the market may be able to supply a panoply of artifacts but it cannot by itself supply what people need the most: A reason to be here, something that justifies waking up every day to do it all over again. What people need the most is meaning and, when you’re a conscious being, meaning doesn’t come from the outside.

Finished in Indio, California.

Speaks to