The Role of Brands in the Commercialization of Experiences

Brands: Particular Ways of Being

How long do you have to go into the movie "Pulp Fiction" until you reassuringly tell yourself, "this is classic Quentin Tarantino"? Like every great director, Tarantino makes use of recurring motifs to infuse his personal brand into his work. His use of extreme close-ups, old-school costumes, and controversial depictions of violence make his films distinctly "his".

Now, imagine you are watching a film of someone's shopping experience. The film is silent, no music or dialogue. You don't know where the protagonist will shop, you only know that they are looking for a new laptop computer. The film starts. How long into the film would you have to go until you realize the protagonist is shopping at an Apple Store?

In an Apple store, the fruit logos are overkill – the brand is everywhere. You can appreciate it on the construction materials, the bright atmosphere, the way the furniture is arranged, and the products themselves. The dynamic inside the store is also unique: The products are there for you to touch and experience. You don't go to the cashier, the cashier comes to you. True to Apple's ethos, the store conforms to the shopper, not the other way around. One could hardly say the same of the experiences offered by department stores like Macy's or Best Buy. Just like watching "Pulp Fiction" and "Reservoir Dogs" are notoriously Tarantino experiences, shopping at an Apple Store is a distinctly Apple experience.

Whenever a provider (e.g., a firm or individual) manages to imprint their brand on an experience in such a unique way, they are providing a "branded" experience. Delivering a branded experience is not simply about making sure the consumer knows who the experience provider is, it is about having the consumer say "there is something very [insert brand] about this experience". In a branded experience, the consumer experiences the brand itself.

Brands Exist in Your Mind

A firm cannot provide a branded experience if it does not have a brand. But what is a brand? In 1998, marketing professor Kevin Keller (Tuck School of Business) provided what seems to now be a classic definition of the term:

"A brand is a set of mental associations, held by the customer, which add to the perceived value of a product or service."

As Keller noted, the nature of a brand is mental. A brand is a construct we use to tie an experiential offering (e.g., a product, service, performance) with a provider. This construct consists of all the mental associations we can make with both, the provider and the experience. It can include names, visual elements, ideas, perceptions, beliefs, attitudes, feelings, moods, sounds, tastes, smells, people, fictional characters, events, and stories, including the brand's own origin story. These associations are established when we pick up information from the environment, from other people, and, most importantly, from our own first-hand involvement with the experience provider and their offerings. Take, for instance, the following map of associations that can be done with Nike as a brand:

- A low resolution model of my mental concept of the Nike brand.

Constructs like brands are stored in what psychologists call semantic memory. The structure of semantic memory is still the focus of intense research, but it is often modeled as a vast network of interconnected concepts. Each node in this network represents a unit of information (e.g., a person, place, logo) stored in our memory. The associative nature of semantic memory makes it so that thinking of a concept in the network can automatically make us think of connected concepts, like a cascade of firing neurons. This effect is known as associative activation.

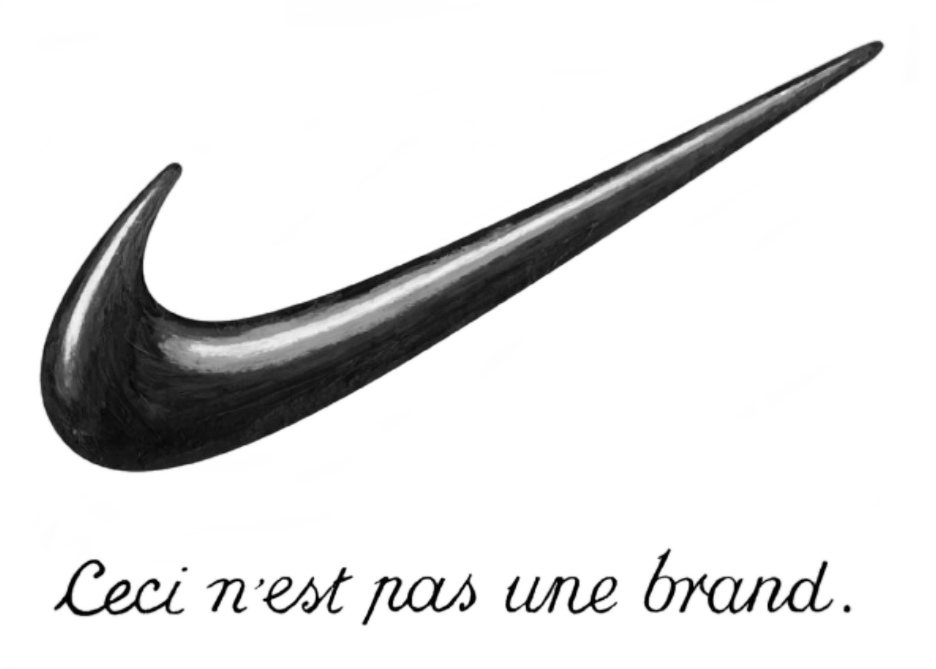

Associative activation is the reason why people conflate brands with their logos. Naturally, the nodes belonging to brand logos and their corresponding names are heavily networked in our mental construct of a brand. That is why logos are commonly used by firms to "invoke" the brand in our minds. Marty Neumeier cleverly points this out in his book "The Brand Gap":

A play on René Magritte's famous "The Treachery of Images"(popularly known as "This is Not a Pipe").

A play on René Magritte's famous "The Treachery of Images"(popularly known as "This is Not a Pipe").

Brands are Socially Constructed

But the brands you know and love don't only exist in your mind, they also exist in the minds of the people around you. Granted, not everyone's mental construct of it will be the same, but there is a shared essence tying them together. This essence is a broader, socially-constructed idea of the brand that is built from people's shared perceptions. It is this collective construct what firms and providers care about building, because that is what gives brands their value in the marketplace. Building upon Keller's definition, prominent marketing executive Nigel Hollis (Millward Brown/WPP) accounts for the social construction of brands in his book "The Global Brand":

"A brand consists of a set of **enduring and shared** perceptions in the minds of consumers. The stronger, more coherent and motivating those perceptions are, the more likely they will be to influence purchase decisions and add value to a business." [Emphasis added]

The social construction of a brand is perhaps its most valuable attribute. It can take decades to build but, once established, it allows providers to earn outsized returns by providing branded experiences at scale.

Brands Form Naturally

Consider music, when is the last time you heard a new song you really liked at a party? Did you find out by who it was? Now consider clothing, have you ever asked a stranger about something they were wearing? What did you ask for? Brands form naturally in our minds because we like to associate experiences with their source. That is why most brands have an origin story that connects them to a product- or service-space. If an experience is unique enough to warrant its own place in your mind, a brand has been born. Even in the absence of a trade name, people will still relate an experiential offering with some aspect of its provider: It's location, the name of the business owner, or any visible symbols.

A peculiar example in brand emergence is that of "El Palacio de Hierro", a chain of upscale department stores in Mexico. The dramatic name, which in English translates as "The Iron Palace", has its origin story in the company's very first store. Passersby would look up as it was built in the 1890s, gazing at the structure's meticulous ironwork. They called it what it looked like, a palace made of metal rising in downtown Mexico City (iron was a common construction material in the 19th century, before steel became the standard in the 1900s). Soon the company realized the name had picked up with the public and secured it as its trademark to capitalize on the name recognition. Through decades of brand-building, the name has since become synonymous with wealth and status in the Latin American country.

An illustration of the original Palacio de Hierro in Mexico City. (Source: Casa Palacio)

An illustration of the original Palacio de Hierro in Mexico City. (Source: Casa Palacio)While brands can emerge accidentally, most brands are "seeded" by the provider. After all, if the consumer is going to associate a product or service with something anyway, the provider might as well offer a "device" (e.g., a name or a symbol) to become depositary for those associations. Still, the effectiveness of the device is up to the consumer. The success and permanence of a name, logo, or visual identity depends on its ability to help people tie together and recall the experiences they have with the brand. Not without reason organizations pay hundreds of thousands (or even millions) to have prestigious design firms like Pentagram, Wolff Olins, or Landor develop a coherent visual identity for them.

Brands Find Definition in Abstraction

Not only do our minds like to associate experiences with their source, they also have a tendency to associate elements that appear concurrently in our experience. Every lived moment that you have involving a brand incrementally defines your mental construct of it, regardless if positive or negative. Advertisements, news articles, public relations scandals, and displays of philanthropy – they all shape our personal construction of a brand, like a chisel cutting through marble. Robert Heath, an iconoclast in the world of advertising research, calls it low involvement processing. From his book "The Hidden Power of Advertising":

"The way our long-term memory works means that the more often something is processed alongside a brand, the more permanently it becomes associated with that brand. Thus, it is the perceptions and simple concepts, repeatedly and ‘implicitly’ reinforced at low levels of attention, which tend over time to define brands in our minds. And because implicit memory is more durable than explicit memory, these brand associations, once learned, are rarely forgotten."

Not surprisingly, the more experiences we have with a brand, the less it is about the experiences themselves and the more it is about the subtleties tying them together. It may be counter-intuitive, but the more abstract the brand gets in our minds, the better defined it becomes. The final goal of any brand is to become a thing of its own, a living collection of shared and hopefully meaningful abstractions. When a brand reaches this state, it becomes a vessel for meaning and an author of experiences.

Brands Manifest Through Media

You may recall from Experience Delivery that people obtain their experiences by engaging a medium. It is not any different with branded experiences: When a consumer engages a brand-infused medium, they have a branded experience.

Branding is the act of infusing a medium with a brand. It goes beyond merely placing a logo or wordmark on a medium. Branding involves finding ways for the brand to become manifest in the medium, along with all that it stands for. When a medium embodies a brand and the meaning it encapsulates, it becomes a "manifestation" of the brand. Brand manifestations offer people a vehicle to engage with the brand, a means to bring that complex mental construct into felt Reality.

- Brands can become manifest through multiple mediums.

Consider a digital product, Google Maps. The service is a true manifestation of the Google brand: It embodies the ethos of the provider of organizing information and making it accessible to everyone. On the other hand, you could hardly say the same of a t-shirt sporting the Google logo. Sure, the logo can invoke the brand in our minds but it cannot deliver a distinctly "Google" experience.

When it comes to brands manifesting through various media, however, the true champions are luxury brands: They manifest through fragrances, stores, cosmetics, clothing, celebrities, fashion shows, and some even in home furniture. Luxury brands operate at the highest level of abstraction that a brand can aim to, that of a "lifestyle", a construct which by definition touches on every aspect of our lives, including the media that we wear and surround ourselves with.

Consider, for example, the brand established by Gabrielle "Coco" Chanel. Born in 1883, Coco Chanel was a woman of humble origins who built a lucrative fashion empire that is still venerated around the globe. Her brand became a symbol of female emancipation through the introduction of the Chanel jacket, an association reinforced through the patronage of influential women like Marilyn Monroe and Jacqueline Kennedy. Writing on her feminism blog, Helena Knidska points out the the brand's significance:

"Coco Chanel single-handedly revolutionized the image of the female body by bringing it back to its natural shape and genuine femininity. Coco literally liberated women - by stripping off the constraints of corsets, she gave them back their right to breathe and introduced a new, modern style of leveraging elegance which women embraced gladly. Sporty, casual chic became the feminine standard of beauty and style - clothes were now made to get you to places, not to restrain you from movement and heading someplace. Chanel was tailored for a bold woman, unapologetic for her womanhood, as its créatrice herself was."

Coco Chanel died in 1971 but her brand lives on. In 2018 alone, people around the world spent $11 billion US dollars to experience the brand through its many products.

Brands Deliver Value

Brands play important functions in a market economy that benefit both, consumers and experience providers.

From a consumer perspective, brands are valuable because they reduce friction and deliver experiential reward: Brands reduce friction because they make it easier to assess and compare the value of products and services, they reduce perceived risk and save us time by setting expectations at the time of making purchasing decisions. From the new version of Keller's "The Strategic Brand Management":

"The problem for most buyers who feel a certain risk and fear making a mistake is that many products are opaque: we can only discover their inner qualities once we buy the products and consume them. However, many consumers are reluctant to take this step. Therefore it is imperative that the external signs highlight the internal qualities of these opaque products. A reputable brand is the most efficient of these signals." (p. 20)

Brands set expectations when they are known for the type of experiences they deliver, they serve as a kind of "guarantee". The Oreo brand, for example, is known for producing its distinctive "cookies and cream" flavor. Whenever a food product bears the Oreo name, whatever it may be, we can expect it to deliver a gustatory and olfactory experience that is distinctively "Oreo". But beyond helping people pick and choose experiences, brands also deliver experiential reward.

By embodying people's aspirations and desires, brands deliver experiences that resonate with consumers at a personal level. they offer internal alignment and validation because they are a means for people to express who they are and who they want to become. They also offer external validation because brands work as a recognizable signal of certain personal traits, goals, and mindsets which can be picked up by other people.

In other words, consumers can "signal" through the brand. From Nigel Hollis's "The Global Brand":

"The significance of the shared understanding is most apparent when considering "identity" brands, ones that openly indicate something about a person's lifestyle and attitudes. The person who chooses a Rolex signals something different about himself from someone who chooses a Swatch. Buying Patagonia clothing makes a different statement from buying Billabong."

A Brand is a Privilege

Brands are coveted by commercial firms because they bring big advantages in the market:

- Brands capture demand from people who don't want to run risks choosing a product and people who don't want to spend time comparing products.

- Brands generate their own demand from people who explicitly seek to experience the brand (e.g., out of loyalty, for validation).

- Brands give brand-owners leverage in pricing because branded experiences are by definition unique and differentiated. In the market, brands are both, a source of differentiation and a moat that keeps competition at bay.

As mental constructs, brands quite literally have a place in the mind of the consumer. This privileged position allows them to capture demand right at the source. Furthermore, brand-owners can leverage their brand to launch new products and services using the brand's existing reputation to give get a leg-up in the market. In "The Strategic Brand Management", Jean-Noël Kapferer talks of brands as a sort of "genome":

"A brand does in fact act as a genetic programme. What is done at birth exerts a long-lasting influence on market perceptions. A brand is both the memory and the future of its products. By understanding a brand's programme, we can not only trace its legitimate territory but also the area in which it will be able to grow beyond the products that initially gave birth to it." (p. 37)

A brand may even chart a path for the owner's entire future. When the brand grows into a firm's most important asset, the firm becomes one with the brand. This is the case of Apple, Nike, and Chanel, names that embody something much greater than the sum of their products: the desire to create, to perform, and being respected, respectively. That is a brand's greatest privilege, to represent our timeless aspirations, those ideas that people will continue paying to experience today, tomorrow, and always.

Speaks to